A Political Interpretation of the Gospel of John, Critically Recounted.

According to Lance Byron Richey, Jesus as the Son of God in John’s Gospel is set against all political-theological claims of Roman Imperial Ideology. Unfortunately, Richey does not conceive of Jesus’ Messianic kingship from the Jewish Torah as the process of liberating Israel and overcoming the Roman world order.

Contents

0.1 Political Interpretation of John by Lance Byron Richey and Ton Veerkamp

0.2 Adolf Hitler as the Self-Proclaimed Heir of the Roman Emperors

0.3 Richey’s Definition of “Augustan Ideology”

0.4 Richey’s Focus on the “Final Redaction” of John’s Gospel

0.5 On the Structure of Lance Byron Richey’s Study

1. Is the Johannine Community “Neither Jew nor Roman?“

1.1 Three Stages of a Johannine Community According to Martyn and Brown

1.1.1 Early Days: A Jewish Sect Turning to Samaritans and Gentiles

1.1.2 Middle Period: Exclusion from the Synagogue and Influx of Gentiles

1.1.3 Late Period: Gentile Mission, too, Encounters Rejection by the “World”

1.2 Are There Firm Conclusions about the Johannine Milieu?

1.2.1 Was Asia Minor the Place of Origin for John’s Gospel?

1.2.2 Did the Number of Gentiles in the Johannine Community Actually Grow?

1.2.3 The Ongoing Conflict of the Johannine Community with the Synagogue

1.3 Was a Jewish Gospel Transplanted into a Roman Context?

2. Augustan Ideology and Its Many Faces of Power

2.1 Augustan Ideology in the First Century

2.1.1 Essential Distinction of Political Power: potestas and auctoritas

2.1.2 The Imperial Cult in Its Political and Religious Dimensions

2.1.3 The Augustan Poets as Ideological Interpreters of Roman History

2.1.4 The Overcoming of the World by Jesus as the Basis for Johannine Criticism of Augustan Ideology

2.2 Exclusion from the Synagogue and Persecution as Challenges to the Johannine Community

2.2.1 „Socio-Legal“ Effects of the Imperial Cult on the Johannine Community

2.3 How Did the Johannine Community Challenge Augustan Ideology?

3. Vocabulary of the Roman Language of Power in the Gospel of John

3.1 The Meaning of exousia, “Power”

3.1.1 Does John by the Term exousia Hint at the Unmentioned axiōma?

3.1.2 Jesus’ exousia in John Is Unmistakable with auctoritas or axiōma

3.1.3 Jesus’ exousia Is Incompatible with the exousia or potestas of the Emperor as well

3.2 How Is Jesus to Be Understood as ho sōtēr tou kosmou, “the Savior of the World”?

3.2.1 The Phrase ho sōtēr tou kosmou in the Roman Imperial Cult

3.2.2 The Role of the Title ho sōtēr tou kosmou in the Samaritan Setting

3.3 Jesus as ho hyios tou theou, “the Son of God,” and the Roman Emperor

3.3.1 Who Is a “Son of God” According to Jewish Thought?

3.3.2 Jesus as the “Son of God” in Paul, in the Synoptics, and in John

4. Christology as Counter-Ideology in the Prologue to John’s Gospel

4.1 Notes on Exegetical Method between Historical and Literal Criticism

4.2 Four Subsections of the Prologue in Their Contrast to Augustan Ideology

4.2.1.2 Is John Developing a Cosmological Christology to Politically Confront Augustan Ideology?

4.2.1.3 A Jewish-Messianic “Cosmology” of the Johannine Prologue

4.2.1.5 Is Jesus Co-Equal with God, while Emperors Remain a Human Creature despite Their Divinity?

4.2.2 Johannine Prophecy in the Testimony of the Baptist (John 1:6-8)

4.2.3 Overcoming the World’s Rejection in the Johannine Community (John 1:9-13)

4.2.3.1 Is ta idia, ”His Own Home,” All Mankind or the People of Israel?

4.2.4 Is the doxa of Jesus His ”Glory” in the Sense of a General Supreme “Divinity”? (John 1:14-18)

4.2.4.1 Jesus as the Only-Begotten God in Opposition to the Roman Emperor

5. Anti-Roman Themes in the Johannine Passion Narrative

5.1 “My kingship is not of this world” (18:36)

5.1.1 Are the Power Spheres of Jesus and the Emperor Dualistically Side by Side?

5.1.2 Is Jesus, Ruling Heaven and Earth, the Superior Overlord of the Roman Emperor?

5.1.3 Is Jesus Refusing to Be a Messiah with Earthly Goals and Thus Not to Be Made King by Force?

5.1.4 Instead of “from This World Order” Jesus’ Kingship is Determined by the Torah

5.2 “If you release this man, you are not Caesar’s friend” (19:12)

5.2.1 The Roman Background of the Expression “Friend of Caesar”

5.2.2 The Choice between Christ and Caesar as Pilate’s Theological Conflict of Loyalty

5.2.3 Pilate’s Superior Position in the Scheme of Intrigue with Jewish Leadership

5.3 “We have no king but Caesar” (19:15)

5.3.2 Are “the Jews” No Longer God’s People Because of Their Decision for Caesar?

5.3.3 Does the Contrast between Christ and Caesar in Fact Imply No Concrete Political Theology?

6. What Kind of Political Theology Is at Stake in the Gospel of John?

6.1 Is Jesus’ Power to Be Understood Autocratically and Implemented by the Church?

6.3 Open Questions of the Historical-Critical Exegesis of the Gospel of John

6.4 Rome-Based Christ or Jewish-Rooted Messiah Jesus?

↑ 0. Introduction

↑ 0.1 Political Interpretation of the Fourth Gospel by Lance Byron Richey and Ton Veerkamp

When, in the course of my intensive study of John’s Gospel since August 2020, I became aware of Lance Byron Richey through Esther Kobel <1> who, according to her, “considers the Gospel’s prologue as a counter-ideology that contrasts Christ with Caesar”, I decided to also include his book on Roman Imperial Ideology and the Gospel of John <2> in my studies, and I do so by contrasting it with Ton Veerkamp’s liberation-theological interpretation of John.

Ton Veerkamp <3>—theologically belonging to the so-called Amsterdam School—assumes that the so-called Johannine dualism neither refers to an otherworldly opposition between this world and the afterlife nor to the demarcation of the new religion of Christianity from Judaism. Instead, the evangelist, who is deeply rooted in the Jewish holy scriptures, is dealing as a Messianic Jew with Rabbinic Judaism, which emerged after the Jewish War and which he accuses of settling down in a niche of the Roman Empire with the privileges of a religio licita, a permitted religion, instead of actively expecting the overcoming of this ruling world order (kosmos) by trusting in the Messiah Jesus and by practicing the solidary love (agapē) he demands. Regrettably, theological scholarship so far does not even begin to consider Ton Veerkamp’s interpretation.

Interesting in this context is a remark made by Richey about his doctoral adviser Julian V. Hills (vii):

I had long been interested in how the political contexts of the gospels helped shape their content, but had previously thought the best way to conceive of this relationship was by using materialist categories, such as those employed by Fernando Belo in his treatment of Mark. While I was casting about for a way to connect the political context of the Fourth Gospel to its theology, my director gently suggested that the approach employed here, rather than the standard tools of materialist exegesis, might perhaps permit me to say something of interest to the scholarly community. While researching and writing, I came to see not only the practical wisdom of his advice but, even more importantly, the relevance of this subject for contemporary political theology (which, however, I have left undeveloped in the present work) and for understanding the unparalleled complexity of Johannine theology.

Perhaps in a synopsis of Richey’s interpretation with that of Veerkamp’s, it may be possible to bring out even more strongly the significance of the theme he raises for political theology.

In addition to a number of overlaps between the two interpretations, significant differences are apparent. Richey accurately describes Johannine Jesus as the great antagonist of the Roman emperor. Unlike Ton Veerkamp, however, he does only half justice to the portrait that the fourth evangelist paints of Jesus, for refers insufficiently to the rooting of Jesus the Messiah in the Jewish Bible. Suppose Jesus confronts the Roman emperor, who also claims divine dignity, with divine authority. In that case, it must be asked from what source he draws the right to be called ho kyrios kai ho theos, “Lord and God,” and what it means in concrete terms that he is proclaimed not only as the basileus tou Israēl, “King of Israel,” but also as the sōtēr tou kosmou, “Liberator of the World.“ In my opinion, Richey does not take seriously enough that

- Jesus must be understood first of all as the messenger of the God of Israel, as the embodiment of his will and work, that is, of his liberating NAME, <4>

- second, the content of Jesus’ kingship is to be filled from the Jewish Bible,

- and third, Jesus primarily focuses on the gathering of all Israel, including the lost northern tribes of Samaria and the Jews driven into the Diaspora, and only then, very cautiously, on “some Greeks” (12:20) who want to see Jesus.

From these premises, I put Richey’s and Veerkamp’s interpretations into discussion with each other supposing mutual enrichment.

↑ 0.2 Adolf Hitler as the Self-Proclaimed Heir of the Roman Emperors

By prefacing the introductory words of his study with the second part of the second thesis of the Barmen Declaration, <5> Lance Richey (xi) makes clear the modern context in which he intends to interpret the confrontation between Jesus and the Roman emperor:

“We reject the false doctrine that there could be areas of our life in which we would not belong to Jesus Christ but to other lords, areas in which we would not need justification and sanctification through him.“

With this thesis, parts of the Protestant Church in the German Reich of 1934 opposed the recognition of Adolf Hitler as God’s providentially chosen Fuehrer of the German people on the road to world domination.

In the final conclusion of his book (187, note 2), Richey will recall,

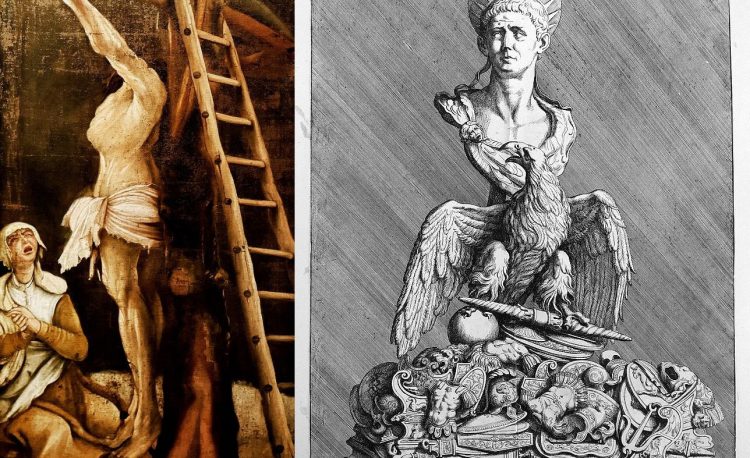

that Hitler in the twentieth century looked back to Augustus as a model and predecessor of the European empire that he hoped to fashion. Joachim C. Fest <6> writes: “It was necessary for Hitler to reject the past because there was no era in German history which he admired. His ideal period was classical antiquity: Athens, Sparta (‘the most pronounced racial state in history’), the Roman Empire. He always felt closer to Caesar or Augustus than to the German freedom fighter Arminius.”

↑ 0.3 Richey’s Definition of „Augustan Ideology“

Nowadays (xi-xiii) “it is largely forgotten” that the sovereign titles sōtēr tou kosmou, “Savior of the world,” and ho kyrios kai ho theos, “Lord and God,” which John’s Gospel applies to Jesus (4:42 and 20:28), were originally claimed by Roman emperors. The “exclusive sense in which they are applied to Jesus” could, according to Richey, risk “persecution, especially during the reign of Domitian (81-96 C.E.), which overlapped with the period when the Fourth Gospel began to receive its final form.”

In this context (xiii), Richey distinguishes “the Imperial Cult” in a narrow sense from “the Augustan Ideology” as „a wide variety of political, social and literary practices”:

The Augustan Ideology developed after Octavian’s ascension to power in 31 B.C.E., which marked the end of the Roman Republic, and effectively reordered the conceptual landscape of the Roman world by establishing the person of the emperor at its new center.

This ideology (xiv)

was a complex and considerably varied set of beliefs, practices and claims about the nature and source of temporal power in imperial Rome. It presented the emperor or princeps as the central figure of the empire on whom the continued peace and prosperity brought by the Pax Romana depended.

Although (note 10) “the Augustan Ideology was not a totalitarian one—at least in the modern sense—which dominated and defined every aspect of private and public life within the empire,” it (xv)

translated on a practical level into a large set of demands on the population of the empire that were both religio-ideological—involving the “mythic” or “imaginative” space claimed by the emperor from his subjects—and socio-legal—pertaining to his more mundane social and political powers.

In this regard, Richey clarifies (note 11):

the Weltanschauung involved in proclaiming Augustus Caesar sōtēr tou kosmou, and the resulting hierarchical conception of both society and the universe, as well as of the place of believers within them, would be “religio-ideological.” On the other hand, any social or political sanctions for the refusal to do so (e.g., execution, punishment, social ostracization) are “socio-legal.”

Since (xv) “there is no plausible locale or timeline for the composition of the Fourth Gospel in which the author(s) would not have been confronted at every turn by the images, practices, and beliefs of the Augustan Ideology,” the Gospel of John must have been “preoccupied with the authority … of the Roman emperor,” and, in Richey’s opinion, all the more so because (xv-xvi)

by the 80s, when the final redaction of the Gospel had begun, the Johannine community had absorbed a large number of non-Jewish converts who presumably would have had personal knowledge of, and perhaps even had participated in, the Imperial Cult.

Of course, the latter assumption is controversial. In particular, it must be asked whether a Johannine community, still focused on the gathering of all Israel without being oriented toward a general mission to the nations, did not have every reason to see itself in sharpest opposition to the Augustan ideology.

↑ 0.4 Richey’s Focus on the “Final Redaction” of John’s Gospel

At the same time, Richey emphasizes (xix-xx) “that the influence of the Augustan Ideology on the Fourth Gospel“ he is proposing

is a relatively indirect one. There was no body of documents constituting the essence of the Augustan Ideology upon which the evangelist drew (though Virgil’s texts perhaps approximate this description). Instead, I suggest that the Roman documents and inscriptions related to the Augustan Ideology express a fundamental way of conceiving the world in the first century that John felt compelled to challenge through his Gospel. No direct literary dependence of the Gospel of John upon particular texts was involved. The Augustan Ideology was less a set of texts confronting the evangelist than the intellectual atmosphere that he and his readers breathed in every day, identifiable through a careful study of relevant texts. The underlying conceptual structure of the Augustan Ideology is found in the Gospel especially when it is being denied or criticized by the author.

It is significant (xx) that Richey wants to limit “the existence of a polemic … against the Augustan Ideology and the grave theological and practical dangers that it posed for the Johannine community” to the “final redaction of John”:

In short, the final redactor(s) of the Gospel wanted to distinguish clearly the nature of Christ’s divinity and power from the religious and political authority of the emperor.

But in Richey’s eyes (note 20), this “last layer of the Fourth Gospel’s literary and polemic sediment … neither erases nor invalidates the literary vestiges of earlier models of Jesus’ messiahship … which may have survived in the text.“ He thinks indeed that the confrontation with the imperial cult and the “Augustan ideology” became significant for the Johannine community only when larger numbers of Gentile Christians joined it. In this situation, then, a new Christology would have overridden the older ideas of Jesus as the Messiah of Israel. Again, it must be critically asked whether John’s Gospel was really revised in this way or whether his entire Christology originally is to be understood as a Messianology <7> that proclaims—based on the Jewish holy scriptures—the Messiah Jesus to be the overcomer of the Roman world order. If so, the Gospel of John would have been reinterpreted only later by an increasingly Gentile-Christian-dominated church in the sense represented by Richey.

↑ 0.5 On the Structure of Lance Byron Richey’s Study

In order to establish his thesis (xx), in the first chapter Richey wants

to situate the Fourth Gospel temporally, geographically and demographically in order to show how the Augustan Ideology influenced its authors and their community and placed them at odds with the surrounding Roman society.

At the same time, he deals with “theories that link the development of the Gospel to increasing conflicts between the community and the synagogue” which “ultimately resulted in the Johannine community being pronounced aposyagōgos (John 9:22; 12:42; 16:2).”

The second chapter serves to examine more closely “the Roman context of the Gospel,” in particular (xxi) “the legal and social demands and expectations” that Augustan Ideology placed on members of the Johannine community who, “once declared aposyagōgos, would have lost the exemption from participation in the Imperial Cult enjoyed by Judaism.“

The third chapter „turns to the vocabulary employed by the Imperial Cult to express and defend the divinity and authority of the Roman emperor,” in order to examine

relevant “pools” of vocabulary associated with both political and divine authority in Roman society and explore how the Gospel of John also contains and critiques these notions of authority.

In the fourth chapter, “John’s Prologue and the initial testimony of the Baptist are interpreted as attempts to contrast Christ with Caesar,” thus making clear “from the very beginning of the Gospel that Christ is totally unlike the worshiped Caesar.“

Three key verses of the Johannine Passion Narrative (18:36; 19:12; 19:15) serve as evidence in the fifth chapter that (xxi-xxii)

John attempts to differentiate clearly the authority claimed by Christ and the rule exercised by Pilate on behalf of the emperor. Rather than interpreting the Passion Narrative as an anti-Semitic diatribe, I suggest that the main opponent is the Roman emperor.

In his Conclusion, Richey suggests that John’s Gospel “should be read as a challenge not only to the synagogue but also to the Augustan Ideology that posed a serious theological and political threat to the Johannine community’s understanding both of Christ and of itself.” Once again he emphasizes the assumption, which I questioned, that

the Johannine community’s encounter with large numbers of Gentile converts unavoidably brought it into contact with the Augustan Ideology. This encounter in turn demanded some clarification of the duties and proscriptions that membership in the community placed upon these converts. It also demanded that the Christology of the community be clearly distinguished from the portrait of Caesar that suffused everyday life in the empire.

↑ 1. Is the Johannine Community “Neither Jew nor Roman?”

In 2007, Richey (1) looks back on forty years of “a renewed interest in the Jewish roots of the Gospel of John, after a generation of studies preoccupied with its Hellenistic and philosophical background.” He focuses his attention (2) on the “key insight” of the exegetes Raymond E. Brown and J. Louis Martyn, <8> that the text of the Fourth Gospel can and should be read as a multi-layered narrative that “tells us the story both of Jesus and of the community that believed in him.”

↑ 1.1 Three Stages of a Johannine Community According to Martyn and Brown

While the attempt (3) is fraught with great “difficulties and uncertainties” to reconstruct “the community’s history from a text that is largely theological in its intent,” (4) “it is just this specifically historical context that is required to understand the Roman influence upon the Johannine community and its Gospel.” In the first chapter of his book, therefore, he seeks “to situate the Johannine community within its historical context,” focusing “in particular on the work of Brown and Martyn,” and drawing out “the most secure results of their researches, especially those that might indicate potential sources of conflict between the community and the surrounding Roman society”:

These scholars agree that the origin of the community that produced the Fourth Gospel was situated firmly within the synagogue. They also hold that the gospel’s subsequent history (and to a large degree the development of its distinctive theology) was determined by the conflicts with and eventual separation from the synagogue. This insight has been one of the decisive factors in the shift from a Hellenistic to a Jewish framework for Johannine scholarship in the latter half of the last century.

What Brown and Martyn agree upon (5), Richey outlines by distinguishing “three main stages in the history of the life of the community.”

↑ 1.1.1 Early Days: A Jewish Sect Turning to Samaritans and Gentiles

In an early phase (5), it represented “a sectarian Jesus-movement within first-century Judaism …, possibly already in conflict with followers of John the Baptist over the identity of the Messiah” and “characterized theologically by a Mosaic understanding of Jesus as a divinely chosen prophet.” This community, “settled in Syria, northern Palestine and eastern Jordan,” (6) “was quickly joined by a group of Samaritans who interpreted Jesus against a Mosaic background as the Messiah sent from God.” Although it still remained “wholly within the bosom of the synagogue,” as Martyn [150] points out, Brown (6-7)

posits an increasing missionary effort among Gentiles as an impetus behind both the heightening of the community’s Christology and the deepening of its division with the synagogue.

Thus Brown seems to infer Gentile missionary efforts by the Johannine community primarily from their alleged consequences, for nowhere in John’s Gospel itself is there mention of a call by Jesus to Gentile mission. I speak of alleged consequences, because what is here called the “heightening of Christology” does not have to be explained by pagan influences, rather the Jewish Messiah Jesus as the embodiment of the liberating NAME of God is to be understood completely from the Jewish biblical scriptures.

↑ 1.1.2 Middle Period: Exclusion from the Synagogue and Influx of Gentiles

In a middle phase, Martyn and Brown say (7), the “theological and possibly ethnic changes among Johannine Christians” led, “by the late 80s,” to an “open schism with the synagogue,” after “peaceful existence within the Synagogue became increasingly difficult” and exclusion “of some Johannine Christians from the synagogue” occurred (8):

Their separation from the synagogue, Brown [56] suggests, became permanent after an influx of Gentile converts joined the community. In this scenario, their admission would have been a logical extension of the community’s previous outreach to the non-Jewish Samaritans. The presence of these Gentiles, according to Brown [55-57], is reflected in the textual reference to a possible mission by Jesus to “the Greeks” (John 7:35) and by the appearance of Greeks (John 12:20-23) as a signal that Jesus’ ministry to the Jews had come to an end. This break with the synagogue, Martyn [155] argues, was possibly accompanied by the subsequent martyrdom of members of the community for ditheism by synagogue Jews (e.g., Jesus’ prediction of persecution in John 15:18-16:4). The result was an increase in the community’s hostility towards “the Jews.”

Against this argumentation, first of all, it must be objected that the turning of the Johannine community to the Samaritans in John 4 is by no means presented as the first station on the way to a Gentile mission, but as a step towards the gathering of all Israel. The woman at Jacob’s Well clearly represents the lost tribes of northern Israel, which together with Judea and the Diaspora Jews constitute the people of Israel. Second, “Greeks” are mentioned only very reluctantly in John’s Gospel and are nowhere explicitly recorded as disciples of Jesus. In this respect, it must also be critically asked whether the Johannine community may indeed already be called “Christian.” The designation “Jewish-Messianic” would be more appropriate. Thus I do not deny the sharpness of the disputes between Messianic and Rabbinic Jews, but definitely a general Gentile missionary orientation of the Gospel of John.

Far from perceiving that the so-called high Christology in the Fourth Gospel has its roots in the God of Israel, uniquely embodied in Jesus, the Messiah and Liberator he sent into the kosmos, Martyn traces its further development back to the “trauma of excommunication and persecution” suffered by the community,

portraying Jesus as a stranger from heaven (e.g., John 3:31) and a dualism between the world “below,” which rejects Christ and the community, and the world “above,” which is the spiritual home of Jesus and the community (e.g., John 15, 17).

Richey goes on to mention a theory put forward by Brown [56-57]

that an influx of Gentiles was either the result or the cause—he is unclear on this point—of all or part of the community relocating to Asia Minor, probably in an urban setting (e.g., John 7:35).

As (8-9) “conflicts with Jews within the synagogue continued to plague the community,” the latter was forced, on the one hand, “to define its Christology in a defensive posture towards Judaism while at the same time it drew upon the religious traditions of the synagogue that it had inherited.”

↑ 1.1.3 Late Period: Gentile Mission, too, Encounters Rejection by the “World”

In its late phase (9), according to Martyn and Brown, the Johannine community,

[h]aving been excluded from and persecuted by the synagogue Jews for their supposed ditheism, … redoubled its efforts at evangelization among the Gentile community, and in the process elevated its Christology.

If, in my view, this assumption alone can hardly be justified from the text of the Gospel, Brown’s [64-65] additional suggestion seems to me all the more strange, that

the hope of greater missionary success here was largely unfulfilled, as the Johannine community proved as objectionable to many Gentiles as it had to the Jews.

If Brown draws the latter conclusion from the absence of any mention of missionary success among the Gentiles in John’s Gospel, then it would seem more obvious that a general mission to the nations was not yet the intention of this community at all.

Richey’s following remarks bring out a little more clearly what Brown is concerned with in his account of the history of the Johannine community:

This effort at evangelization, Brown [57] argues, was significant for the development of Johannine Christology despite its ultimate failure, since its demand that Jesus be presented “in a multitude of symbolic garbs” may also have helped break down the community’s awareness of “worldly” distinctions. This, in turn [Brown 62-91], led to a greater emphasis on the universal significance of Jesus for all believers regardless of group or place of origin. Ultimately, though, continued persecution by the (now Diaspora?) Jews, paired with greater missionary contacts with and frequent rejection by Gentiles, caused the Johannine community to develop and heighten their Christology even further. As a result, they separated themselves more clearly from “the Jews” and “the World” of the Gentiles who had rejected Jesus.

The “multitude of symbolic garbs” that Jesus wears in John’s Gospel may refer to the various titles of majesty he ascribes to himself or are attributed to him: Messiah, King, Prophet, Son of Man, Son of God, Only Begotten, Messenger of God, Logos, Savior, Lord and God. In my eyes, however, all these terms need not go back to Gentile missionary efforts but can be understood, appropriately interpreted, entirely from the Jewish Bible.

Not quite clear to me is what Brown means by the breakdown of “worldly” distinctions that might have been brought about by the transfer of some of these “garbs” to Jesus. Since the following sentence speaks of “a greater emphasis on the universal significance of Jesus for all believers, regardless of group or place of origin,” he seems to have in mind, without wanting to address it explicitly, the overcoming of Jesus’ bias within the ethnic limitations of Judaism. On the contrary, could the Johannine Jesus not have been concerned with the gathering of Israel and, on the other hand, with the overcoming of the Roman world order?

Different speculations are made by Brown and Martyn (10), as to whether “this reshaping and elevation of its Christology to appeal to Gentiles may have caused serious divisions and even schism within the Johannine community itself, as it could tend towards docetism” because through deifying Jesus too much, “the true humanity of Christ” was called into question.

Whether or not an internal schism over Christology occurred within the Community …, by the time the Gospel assumed its final form it reflected a community that had experienced a double alienation from both the synagogue that provided its initial matrix and the Gentile world that had largely rejected its efforts at evangelization.

In this regard, Richey writes in summary (11):

A full appreciation of this sense of alienation from the surrounding world is essential for understanding the threats to the community’s existence and its Christology.

In my opinion, on the other hand, the entire outline of the history of the Johannine community reconstructed by Martyn and Brown is built on questionable premises. It disregards the depth of the rootedness of John the Messianic Jew in the Jewish Bible and proceeds from the false assumption of a general mission to the nations in John’s Gospel. Therefore, the Johannine “Christians” are allegedly confronted with both “Jews” and “Gentiles” as a hostile “world,” and the kosmos, as Rome itself understands it, namely as the “world order” or well-ordered Pax Romana, cannot come into view, which in truth, however, in the eyes of the Jewish Messianist John, represents a worldwide order of violence or new Egyptian slavery, to be overcome by the Messiah of the God of Israel in a new Passover event of liberation: the death of Jesus on the Roman cross.

↑ 1.2 Are There Firm Conclusions about the Johannine Milieu?

Whatever view may be taken of Martyn’s and Brown’s attempts to reconstruct a history of the Johannine community, Richey considers it possible (12) to extract from them “some basic facts about the Johannine milieu that can serve as a secure foundation for further research”:

Of course, the search for a few secure points of reference within the history of the Johannine community is a considerably more modest goal than the reconstruction of its history, but as is often the case in studying the Fourth Gospel, the less presupposed, the better. Only a few of the details from these scholars’ theories need be correct to support the thesis that the Augustan Ideology posed serious challenges to the community and that a response to it may be found within the text of the Gospel.

These “few ‘points of reference’” do not, according to Richey (13), represent “arbitrary” assertions, but

they constitute the bare-boned but most secure underpinnings of any coherent and comprehensive theory of Johannine origins that can both account for the Gentile and Jewish elements present within the Gospel and provide a comprehensible and plausible social setting for the expression of anti-Roman impulses.

↑ 1.2.1 Was Asia Minor the Place of Origin for John’s Gospel?

Traditionally, Ephesus was thought to be the location where John’s Gospel was written since it was assumed (14) “that the author of the Gospel also composed Revelation.” Those (15) who rediscovered “the Jewish context of the Fourth Gospel in the mid-twentieth century” concluded (for example Brown [39])

that the origin of the Johannine community within the synagogue, alongside probable connections to adherents of John the Baptist, “certainly points to the Palestine area as the original homeland of the Johannine movement” (emphasis added).

But despite acknowledging “some Palestinian influence on the Gospel,” Richey considers it

equally clear that the Gospel was not the product of an exclusively Palestinian environment. Even if the community originated there, it must have been dispersed geographically at later stages.

To this end, he firstly resorts to Smith’s <9> argument (16) “that only after 70, and especially outside Palestine, would synagogue membership be the decisive mark of Jewish identity.” That this is true “especially” does not exclude, however, that after the destruction of the Temple, the synagogue also gained greater importance within Palestine.

Secondly, Brown [98] assumes, according to Richey, that

the existence of the Johannine epistles reveals the need for correspondence between different and presumably geographically separated Johannine churches, although the debate over inhospitality in 2 and 3 John suggests they might have been no more than different Johannine “house churches” within a common metropolitan (Ephesian?) area.

Both of these cannot be ruled out, but they do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the time or the place of origin of the Gospel itself.

Thirdly (16, note 42), according to Brown [40-41], it is strange, for instance, in John 9,22 that John has

Jesus and the Jews around him refer to other Jews simply as “the Jews” – for the gentile readers the Jews constitute a different ethnic group and another religion (and often they think of Jesus more as a Christian than as a Jew!). But to have the Jewish parents of the blind man in Jerusalem described as “being afraid of the Jews” (9:22) is just as awkward as having an American living in Washington, DC, described as being afraid of “the Americans”—only a non-American speaks thus of “the Americans.”

This distancing way of speaking about “the Jews” in John’s Gospel is indeed a major problem, but it need not necessarily be due to the fact that the Gospel was written from a non-Jewish perspective. Likewise, it is possible that the Johannine Messianic Jews, who trusted in Jesus as the Messiah, used this term to refer to the Rabbinic leadership of the synagogue that emerged after the Jewish War as opposed to them. Moreover, in John’s Gospel, the Messianic community seems to be especially anchored in Transjordan, Samaria, and marginal Galilee, and also from there to be opposed to the Jewish elite from Jerusalem and surrounding Judea.

Antioch has also been considered as the place of origin of John’s Gospel. Richey can imagine that (17)

the Johannine community, as it moved to Antioch and then to Ephesus, would have come into closer and closer proximity to—and greater and greater conflict with—the Imperial Cult, since its presence in Asia Minor was stronger than in any other region of the Roman Empire.

All in all, Richey comes to the ultimate conclusion (17-18):

The Johannine community, at least in its later stages when the Gospel received its final form, was evidently located not in rural Palestine but in a major metropolitan center, probably in Asia Minor. Whether in Ephesus or Antioch (or both), the Johannine community was situated within the cultural sphere of Asia Minor where the Augustan Ideology and especially the Imperial Cult were most prominent in the empire. Close contact and conflict with it would have been unavoidable. Moreover, whatever particular geographical choice is made by exegetes, the Johannine community would still be found within a society controlled by Rome and infused with the symbols and practices of the Augustan Ideology.

Against Richey’s considerations is what Monika Bernett <10> published about the “Imperial Cult in Judea under the Herodians and Romans” in the same year as Richey’s book was published. According to her, the cult dedicated to Emperor Augustus was already omnipresent in Palestine since Herod the Great:

King Herod was among the first who, after Actium, in C. Caesar (Augustus) exalted the new ruler in Rome and in the Imperium Romanum in cultic form and thus participated in the symbolic structuring of the new political form of rule in Rome. The prelude still took place in Jerusalem in the early summer of 28 B.C. with the foundation of a Penteterian Agon {competitions held every five years} (Kaisareia) in honor of C. Caesar. A year later Herod refounded ancient Samaria as the polis Sebaste, probably the first eponymous {named after the emperor} city for C. Caesar Augustus in the Roman Empire, and also erected a temple to Augustus there. This was followed a few years later by Caesarea [Maritima], the second eponymous city foundation for the Roman princeps in Judea. The city received a monumental temple to Roma and Augustus and quadrennial cult games. Herod finally built a third temple in 20 B.C. in the north of his empire, expanded in the same year, near an ancient natural sanctuary of Pan, at the foot of Mount Hermon, and near one of the Jordan springs.

In research, little attention has been paid to this process so far. There is no independent treatment of the Imperial Cult as established by Herod (40-4 B.C.) in his empire and as it then developed under the political heirs of his empire—the sons Archelaus, Antipas, Philippos, the grandson Agrippa I, the great-grandson Agrippa II, not to forget the Romans in direct rule over Iudaea (6-41 C.E., then again from 44 C.E.).

If we add that John is the only evangelist who uses the Roman name “Sea of Tiberias” for the Sea of Galilee, we can imagine that within Palestine, not only in the capital Jerusalem or in the imperial city Caesarea but also in Galilee, the presence of the emperor was not much less felt as a constant challenge than in Asia Minor.

↑ 1.2.2 Did the Number of Gentiles in the Johannine Community Actually Grow?

Richey suggests (18) that the question of the place of origin of John’s Gospel cannot be answered without at the same time asking about “Gentile presence within the Johannine community and continuing Jewish hostility to it.”

He first refers to Brown [56-57], who (19)

argues that the reference to Hellēnes in 7:35 (as well as in 12:20—notably the only two places in all four Gospels where the word appears) is an attempt by the evangelist to justify the community’s acceptance of a large and ever-increasing number of Gentiles by retrojecting the process to the ministry of Jesus.

I think it is problematic that many scholars are considering back and forth whether John 7:35 refers to a possible teaching activity or mission among Gentile Greeks or perhaps only among Diaspora Jews, although the corresponding sentence is put into the mouth of Jesus’ Judean opponents, who misunderstand his announcement that he will withdraw into the hiddenness of the FATHER, where they cannot come. If the Gospel of John really presupposes a mission to the nations on a larger scale, wouldn’t there have to be a confirmation of it also in the mouth of Jesus? Wouldn’t there have to be at least a mention of the inclusion of one or the other of the Greeks, who want to see Jesus according to 12,20, into the ranks of Jesus‘ disciples?

That (20) “a mission to the Gentiles by Christians after Jesus’ death is a matter of established fact,“ as Richey puts it, contains some inaccuracies. First, the name “Christians” for the followers of Jesus is formed only in the course of time, when the communities trusting in Jesus become more and more alienated from Judaism as another religion. Second, although Paul’s ministry from the beginning is directed toward a mission to the nations and toward the establishment of congregations in which Jews and Gentiles (goyim, “members of the nations”) together form the Messianic community, the body of Christ, there continue to be congregations that see themselves as Jewish and trust in the Messiah Jesus without turning to the mission to the Gentiles on a larger scale.

That Martyn, for example, “pays almost no attention to the question of Gentile presence within the community” is unfortunate in Richey’s eyes. He attributes this to paying too little attention “to the notion of ‘the World’ in the Fourth Gospel.” Brown [63], on the other hand, “takes ‘the World’ to refer specifically to non-Christian Gentiles and not at all as virtually identical to ‘the Jews’.” From this, Brown [65] draws conclusions already mentioned in section 1.1.3 (21):

“What I would deduce from the Johannine references to the world is that, by the time the Gospel was written, the Johannine community had had sufficient dealings with non-Jews to realize that many of them were no more disposed to accept Jesus than were ‘the Jews,’ so that a term like ‘the world’ was convenient to cover all such opposition.”

This identification of the “world” mentioned in John’s Gospel with concrete non-Jewish people is, however, only a mere assumption. That the term kosmos, “world,” in John’s Gospel can also be understood in a completely different way, namely in the sense of the Roman “world order” under which Israel is enslaved together with many other peoples, will be explained in more detail in section 4.2.3.1 in connection with my note 84 by a quotation from Ton Veerkamp.

Richey, on the other hand, cites another argument for an “early appearance of Gentiles within the Johannine community.” In his eyes, this

also makes sense on a sociological level. The impending or actual separation from the synagogue and continuing hostility of the Jews that the Gospel clearly reveals (see below) would have increasingly limited the availability of Jewish converts whom the community needed to grow and survive. This may have been realized relatively early in the history of the community, along with the fact that the only other possibility for new members would have been the Gentiles among the Diaspora. Even without any textual evidence for the inclusion of Gentiles within the community, such an assumption would make sense based on what we know of other Jewish-Christian churches of the period.

Significantly, Richey refers in this regard (note 59) to a study <11> of the Gospel of Matthew, in which Jesus actually urges his disciples to bring the Torah of the Jews, as Jesus teaches it, among the nations (Matthew 28:19-20). Corresponding (21) “textual evidence,” however, is entirely absent from John’s Gospel, while there is clear evidence that the Johannine Jesus focuses on the goal of gathering and liberating all Israel, including the tribes of Samaria (John 4 and 10:16) and the Diaspora Jews (John 11:51-52).

The fact that the number of Jesus’ followers shrinks more and more in the course of time is thematized in John’s Gospel itself, but it is not compensated for by missionary efforts to the nations. Instead, even Jesus’ mere contact with the Greeks who want to see him (12:20) is only possible by way of mediation through his Jewish disciples, without this itself being explicitly mentioned. After even the first two encounters of the disciples with the risen Jesus take place in the smallest circle behind closed doors (20:19, 26), it is only in the last chapter that we are told of the Johannine community breaking out of its “sectarian isolation” and of its “connection to the synoptic Messianism” by recognizing Peter as the shepherd of the community. <12>

Richey, on the other hand (21), takes it as “likely”

that the Johannine community began to attract Gentile members before any “official” break with the synagogue, and before the Gospel reached its final form…

Even as he tends (21-22) to question

particular details of Brown’s theory, one of its greatest strengths is the fact that it cuts the Gordian knot within the text itself: it explains the strongly Jewish elements at the heart of the Gospel and accounts for the setting of the final version of the Gospel and of the Epistles within a community that was increasingly, if not predominantly, Gentile. In sum, the presence of relatively large numbers of Gentiles in the community by the time the Gospel was produced can be assumed.

Richey’s conclusion, however, stands on feet of clay in my view, judging from the few foundations on which he builds it.

↑ 1.2.3 The Ongoing Conflict of the Johannine Community with the Synagogue

Hardly anyone would deny (22),

that throughout its history the community that produced the Fourth Gospel found itself in conflict with the synagogue, or that this conflict appears in the text itself (e.g., 9:22; 12:42; 16:2).

Moreover, as Richey puts it,

there is no doubt that before the end of the first century a final and irrevocable rupture had occurred between Jews and Christians.

That Richey refers to the parties involved in the conflict as “Jews” and “Christians” narrows down from the outset the possible causes of this rupture to the opposition of two religions separating from each other. What does not come into view is the possibility that two Jewish-rooted factions, namely Messianic Jews, trusting in the Messiah Jesus, and Rabbinic Jews, relying solely on the Torah of Moses, could be involved in an inner-Jewish dispute with each other.

After all, unlike many adherents of Martyn’s and Brown’s outlined history of the Johannine community (note 61), Richey emphasizes

that the conflict was certainly a “two-way” affair, that is, Johannine Christians were not mere passive victims of “the Jews” but probably instigators as well, at least as “thorns in the side” of the Jewish leaders, with their anti-synagogue polemics. The numerous warnings among post-World War II scholars against anti-Semitic readings of the Fourth Gospel should not be forgotten in the account of Jewish-Christian relations underlying my reading of the Gospel.

In any case (23), this hostility preceded the break between the Johannine community and the synagogue:

Conflict with the synagogue was hardly unique to the Johannine community during the first century, but could be found throughout the early history of Jewish Christianity.

In particular, Richey mentions “Paul’s claim that ‘five times I have received at the hands of the Jews the forty lashes less one’ (2 Cor 11:14),” and he does not see any “reason to think the Johannine community was spared these experiences.“ Likewise, it is clear (24):

No group unnecessarily creates a schism within its ranks. Rather, it was the last resort in a long and painful internal struggle.

But as to what exactly necessitated the schism, I find few concrete answers in Richey’s discourse, except that “two of the Synoptics ascribe the immediate cause of Jesus’ betrayal and execution to Jewish authorities.” He concludes this section as follows (25):

In short, from its earliest stages until the time when the Gospel received its final form, the Johannine community found itself in conflict with the Jewish authorities in the synagogue and under the threat of various forms and degrees of persecution by them. This situation gave impetus to the tendency towards separatism, which the influx of Gentiles into the community had already set in motion and which probably manifested itself in the geographical relocation of the community from Palestine to the more cosmopolitan region of Asia Minor.

↑ 1.3 Was a Jewish Gospel Transplanted into a Roman Context?

Although after “the work of Martyn and Brown, no one seriously questions the deeply Jewish character of the Fourth Gospel,” according to Richey, however (25-26),

it is not only Jewish in its background or interests. Rather, it reflects a wider range of influences and concerns. The history of the community that has been sketched out here, with its trajectory from the synagogue to the Gentile communities of Asia Minor, suggests another context as well, specifically, a Roman one that would prove just as objectionable and inhospitable. In Chapter Two we consider the possibility that the Jewish authorities employed Roman law as a weapon in their fight against Johannine Christianity.

Thus, Richey’s observations in his first chapter on the history of the Johannine community basically do not come to the conclusion he implies in the title, namely that this community is to be classified as “neither Jewish nor Roman,” but rather that it has both Jewish roots and is exposed to Roman influences. The question of whether in the Gospel of John, there is already a “Christian” self-understanding in relation to the Jewish religion or whether a Jewish-Messianic self-understanding is still to be presupposed, will have to be thought about further.

↑ 2. Augustan Ideology and Its Many Faces of Power

What (27) “is now called the Augustan Ideology,” was the key to “success” in a challenge Octavian faced after “his defeat of Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31. B.C.E.” He “set about reordering the Roman political and social order to avoid the political unrest, assassinations, and civil war that had brought Rome to the brink of ruin.” Since he was “declared Augustus in 27 B.C.E.,” it has become common to refer to him by this title. The “Augustan Ideology” completely

overturned the conceptual landscape of the Roman Republic and laid the foundation for a unified and dynamic imperial system by establishing the person of the emperor at the center of the new order.

According to Karl Christ, <13> this ideology

did not simply secure the position of Augustus as the current ruler over the Roman Empire, but its “slogans also preached integration; they helped strengthen the system and make it fast; they gave prominence to the chosen successors of Augustus, and were a decisive factor in identifying the family of the princeps with the state.” It was perhaps the decisive factor in the formation of the Roman world and thus for the growth of Christianity, including the Johannine community.

↑ 2.1 Augustan Ideology in the First Century

In the first part of the second chapter (27-28), Richey intends to

examine the three main areas of Roman life that were essential for the rise and consolidation of the Augustan Ideology: (1) Augustus’ supreme political position and the structures that he and his successors used to exercise control over the empire of the first century; (2) the Imperial Cult, which arose during the reign of Augustus to justify and buttress the position of the emperor in Roman society by making him the object of popular religion; and (3) the aptly-named “Augustan poets,” especially Virgil, whose works helped to connect the role of the emperor to the heroic past of the Roman people. As will be shown, the cumulative effect of these three manifestations of the Augustan Ideology was not merely to secure the political position of the Emperor within Roman society. Rather, it resulted in the creation of a new and distinctively Roman Weltanschauung, which situated the inhabitants of the empire not only in respect to the emperor but within the larger cosmos as well.

According to Richey, this prevailing ideology

presented a serious threat to the Johannine community, since the community could neither accept nor participate in the Augustan Ideology, nor could it claim a legal exemption from doing so because of its excommunication from the synagogue.

↑ 2.1.1 Essential Distinction of Political Power: potestas and auctoritas

Formally (29), “the official and publicly recognized legal power” vested in Roman emperors since Augustus referred to the official power of a tribune of the people, as “his tribunicia potestas.” With great political foresight, Augustus,

[t]hrough the constitutional settlement of 27 B.C.E. Augustus officially surrendered the broader dictatorial powers previously granted him during and following his contest with Antony… Thereafter he intentionally limited his still enormous potestas to forms that were putatively continuous with the republican constitution and exercised it with a limited but still meaningful degree of consent and advice from the Senate…

It was not until (30) Caligula, Vespasian, and Titus “that these ‘official powers’ of the emperor began to shatter the molds imposed by the republican tradition.” Remarkably, according to Richey (note 5)

the reigns of Vespasian (69-79 C.E.) and Titus (79-81 C.E.) immediately preceded the period during which the composition of John occurred. They clearly constitute a period of aggressive expansion in imperial powers that would have further imposed the personality and figure of the emperor upon his subjects.

Since, according to Richey (30), the

potestas of the emperor, however, was never sufficient by itself to rule the empire of the first century…, even when expanded quite beyond traditional republican boundaries…, Augustus made auctoritas a central component of his mode of governing.

Formally (note 7), even here

we find Augustus working out of the republican tradition, at least nominally, since under the republic auctoritas had referred to “an informal decree of the senate” or “a proposal made by an individual senator.” <14>

But in practice (31), auctoritas, according to Karl Galinsky, <15> is

“part of a para- or supraconstitutional terminology (other such terms are princeps, pater patriae, and even libertas) by which Augustus bypassed or, on a different view, transcended the letter of the republican constitution.” This auctoritas, in turn, was based—indeed, defined by—Augustus’ “personal influence or ascendancy.” [Latin, 12] John Buchan more generally describes it as “a status won by strong men in all ages despite the forms of a constitution.”

In the background of Augustus’ auctoritas as “an amorphous and informal influence based not on legal statute” were

his personal client-relationships with numerous individuals inside and outside of the official governmental structure. There was precedent for this use of the clientele-structure by Julius Caesar, who administered Gaul solely through his auctoritas, and a major factor in Augustus’ triumph over Antony was “his mobilisation of [Julius] Caesar’s clientela” [thus Christ 49]. It is not surprising that under Augustus the client-patron relationship became the decisive element of how his auctoritas functioned in Roman political culture, since its application to the state repeated a more basic pattern of human relationships which organized Roman society at every level.

This is how (note 13) Garnsey and Saller <16> “describe the centrality of Patronage to the Roman social order”:

“The place of a Roman in society was a function of his position in the social hierarchy, membership of a family, and involvement in a web of personal relationships extending out from the household. Romans were obligated to and could expect support from their families, kinsmen, and dependents both inside and outside the household, and friends, patrons, protégés and clients.”

Also (31-32) in “the case of the emperor, this client-patron relationship” was no one-way street; rather (32), it was a link of

the emperor to his subjects not merely on a transactional basis but also, ideally, on a deeper level of loyalty and trust. In this respect, the emperor’s auctoritas was part of what made him a leader as opposed to a mere official (however powerful).

As a vivid example (note 14) of “the informal yet powerful influence of auctoritas,” Sherwin-White <17> cites “Paul’s appeal to Caesar in Acts 26:32”:

Equally when Agrippa remarked: “This man could have been released if he had not appealed to Caesar,” this does not mean that in strict law the governor could not pronounce an acquittal after the act of appeal. It is not a question of law, but of the relations between the emperor and his subordinates, and of that element of non-constitutional power which the Romans called auctoritas, “prestige,” on which the primacy of the Princeps so largely depended. No sensible man with hopes of promotion would dream of short-circuiting the appeal to Caesar unless he had specific authority to do so.

Brunt and Moore <18> (32) aptly explain the difference between potestas and auctoritas:

“With potestas a man gives orders that must be obeyed, with auctoritas he makes suggestions that will be followed.“ Thus, publication—or, when necessary, invention—of those qualities in the personal character of the emperor that represent him as a reliable and trustworthy patron became one of the most important functions of the Augustan Ideology.

Augustus himself (33), in the account of his life’s work, Res Gestae Divi Augusti, “The Deeds of the Divine Augustus,” <19>

writes of his sixth and seventh consulships: “After this time, I excelled all in influence (auctoritate), although I possessed no more official power (potestatis) than others who were my colleagues in the several magistracies.”

↑ 2.1.2 The Imperial Cult in Its Political and Religious Dimensions

It is precisely this last-mentioned document, Res Gestae Divi Augusti (34), written by Augustus himself, that was “was read to the Senate by Tiberius’ son at Augustus’ funeral in 14. C.E.” in order to ground, as Gradel <20> says, “the old emperor’s argument, his apologia, for receiving his crowning honour, state divinity, which he had modestly (or prudently) rejected throughout his lifetime”:

The Senate’s decision to declare Augustus a god and to establish his cult had benefits for the empire that stretched far beyond the posthumous gratification of his vanity.

Rather, it was advantageous for the empire (34-35) that in this way “Augustus’ auctoritas, upon which the Augustan Ideology had placed the burden of Roman stability and prosperity,” did not die with him:

In other words, establishing, honoring and promoting the cult of Augustus allowed subsequent emperors to preserve and draw upon his auctoritas in order to solidify the system of governance that he had built during his lifetime. The subsequent establishment of cults for Augustus’ successors were modeled on his, and were properly perceived as building upon and continuous with his auctoritas rather than as challenges to it.

According to Richey (36), this “legitimating function was especially important in the newly conquered Eastern provinces of the Roman Empire.” He cites Simon Price’s <21> convincing account, “that the Imperial Cult helped to form a symbiotic relationship between Rome and the Asian Provinces.” Yet (37) “the complexity of the Imperial Cult’s function in Asia Minor as a set of practices” defies “categorization as either purely political or purely religious.”

In this context, Richey takes a critical view of an interpretation of the Imperial Cult that “reflects a very Christian … understanding of religion as essentially or even exclusively concerned with ‘interiority’ as the criterion of authenticity,” as advocated, for example, by Helmut Koester: <22>

The cult of the emperor was part of the official Roman state religion, it never became a new religion as such, or a substitute for religion. … Certainly, people were grateful for the establishment and preservation of peace by the emperor, and they hoped that the gods or the powers of fate would continue to enable the emperor to secure peace and prosperity. But this did not imply that this Roman empire could be the fulfillment of the religious longings and spiritual aspirations of mankind.

Richey, on the other hand, resists treating the Imperial Cult exclusively

as a political, sociological, or cultural practice. However, with the exception of some educated and philosophically inclined elites, the contrast between “interior” and “exterior” religion was hardly a central one for the first-century mind, if it existed at all.

Quoting (38) Géza Alföldy, <23> Richey even emphasizes “that the success of the Imperial Cult ultimately depended upon its ability to meet the sincere religious needs of everyday people,” centered around the concept of salus, meaning something like well-being, salvation, security, health:

First, even if the worship of the emperor might upon occasion have amounted to nothing more than adulation or political calculation, or even if it was sometimes mere hypocrisy, there can be no doubt about the widespread conviction that the ruler was a god, or was at least something like a god. His insuperable and therefore divine power, at once a very real and present force for most of his subjects, was regarded by these people as the guarantee of their salus. Moreover, to secure the continual operation of this power, it was necessary to fulfill the demands of cult—with prayers, victims, and further rites—in the same way as one might acquire the help of other gods. The only difference was that the emperor was also a human being, liable to illness and death, i.e., he could guarantee the salus of his subjects only when his own salus was secured. Precisely this double nature of the ruler, however, magnified the importance of his cult. On the one hand, it was necessary to honor and adore him; but it was also essential to sacrifice for his safety. In other words, one sacrificed not only to him as a god, but also for him as a man.

Furthermore (39), “these prayers for the salus of the living emperor” can be seen as the client’s “fulfillment of yet another duty … towards his patron as payment for the salus received from him.” In this regard, Steven Friesen <24> writes:

Thus, the double prayer—to the emperor and to the gods on behalf of the emperor—does not reveal a deep-seated ambivalence at the heart of the imperial cult. Rather, the twofold prayer accurately reflected imperial theology: the gods looked after the emperors, who in turn looked after the concerns of the gods on earth to the benefit of humanity. Imperial authority ordered human society, and divine authority protected the emperors. That is why the prayer to the emperors was a petition regarding various personal affairs, and the prayer to the gods was simply for the continued well-being of the emperor.

The extent to which “devotion to and intercession on behalf of the emperor” was also widespread “outside of the public cult” is difficult to say for lack of evidence (39-40):

Nevertheless, Ittai Gradel [198-212] argues for at least some standardized forms of private cult based on the presence of frescoes and murals in private residences. Similarly, Duncan Fishwick <25> has argued for an established set of private devotional practices associated with the Imperial Cult, involving the offering of wine and incense to the Emperor on a daily basis within the household.

But even (40) if there was no such “private devotion to the emperor,” the Imperial Cult still posed a threat “to early Christians”:

Whether someone worshiped the emperor in the temple or in the home, the act involved the worshiper in a larger ideology that integrated secular power and divinity, as well as the individual’s relationship to both. That was one of the most vexing problems confronting Christians in the first century, and the Johannine community may have felt it more keenly than any other Christian group of its day.

↑ 2.1.3 The Augustan Poets as Ideological Interpreters of Roman History

Finally, as a third element of Augustan Ideology (41), after the “Imperial Cult” that “situated the subjects of the Emperor ‘vertically’ in relation to the gods, and the emperor’s auctoritas” that “situated them ‘horizontally’ within their society,” Richey refers to “the work of the Augustan poets, especially Virgil,” who “did so ‘diachronically’ through the representation of Roman history“:

[T]heir poetry presented Augustus not only as the inheritor of the republican traditions of Rome but also as the bearer of the historical destiny of the Roman people. To that extent, their work was very important for both the Imperial Cult and the notion of Augustus’ auctoritas, and it provided a central support for both. By means of the Augustan poets, the imperial system established by Augustus came to be understood not merely as a fortuitous resolution to the crises of the first century B.C.E. but as the fulfillment of an inevitable and divinely ordained historical process.

In our context (42) the “most important of these ideas … is the glorification—indeed, the divinization—of Julius Caesar and Augustus by the Augustan poets”:

The clearest example of this “literary-mythic” aspect of the Augustan Ideology is found in work of Virgil. Virgil’s magnum opus, the Aeneid, was begun at Augustus’ request after his victory at Actium and famously saved from the flames by imperial order following the poet’s premature death in 19 B.C.E. From the flight of Aeneas from fallen Troy in Book 1 to his slaying of Turnus at the mouth of the Tiber (Book 12), the Aeneid provides a mythical past for the Romans that is nothing less than a “theology of history” or, better yet, theodicean epic. <26> The weight of this task is reflected even in the somber tone of the poem, “a mood very different from the joyousness of Homer. For the burden the Aeneid carries is no less than the history and destiny of Rome and, in a sense, the world.”

According to Richey, Virgil “lays the groundwork for the Imperial Cult” not only (42-43) “by emphasizing the divine origin of the Julio-Claudian house, specifically with the idea of presenting Aeneas as the offspring of Venus,” but also (44) by portraying “Augustus as chosen by Jupiter to establish a universal Roman empire and to rule over a renewed golden age.” <27>

Also (45) “in Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue, often called the ‘Messianic Eclogue,’ because of its prophecy of a Golden Age that would be inaugurated by the birth of a child,” is found the “motif of Augustus as divinely ordained leader.” Its unique feature is (46) “to project the Golden Age into the future rather than in the distant past, as was the common practice in the Roman world,“ and to identify “its inauguration with the birth of a child.” This later “resulted in centuries of christianizing interpretations of the poem,” but in “its solemn and prophetic tone” it could be readily applied to the person and reign of Augustus in the first century, especially “with an audience that considered prophecy an important and interesting part of life.” <28>

In addition to Virgil (47), Richey discusses the poet Horace, who, among other things “places Augustus second only to Jove in power as lord of all the earth.” Both poets (48) were so popular that they “played no small part in the propagation of the Augustan Ideology among the educated classes, at the very least.”

The poet Propertius (49)

on the other hand, reveals the darker side of the Augustan Ideology, with its unparalleled concentration of power in one person and its sweeping reorganization of traditional Roman society. … While Augustus’ military triumphs are duly praised … and prayers are offered for his health in order to secure Rome’s triumph …[, r]ather, the underlying theme of Propertius’ poem is the precarious position of the individual under Augustus and his ideology.

It is the work of Propertius that, according to Richey, expresses the problem that Augustan ideology must have posed for the Johannine community (50):

Here we find expressed the essential problem of the Augustan Ideology for the first century. Augustus truly had saved Rome from destruction in the civil wars and had brought a real measure of peace and order to the empire; for these accomplishments the Augustan Ideology duly exalted him. Because of its ubiquity, hegemony within Roman Society, and its penetration into personal life, the Augustan Ideology typified the “Caesarism” that Oswald Spengler called a “kind of government which, irrespective of any constitutional formulation that it may have, is in its inward self a return to thorough formlessness.” <29> The price paid for peace was, in the minds of many (if not on their tongues), perhaps too great. If even so educated and well-placed an artist as Propertius could only indirectly lament its influence, how much greater must have been the tensions and difficulties of a dissident group such as the Johannine community.

↑ 2.1.4 The Overcoming of the World by Jesus as the Basis for Johannine Criticism of Augustan Ideology

According to Richey (50), “the Roman context of the Fourth Gospel” can only be understood by grasping how through “Augustan Ideology”

the most important strands of the individual’s life (family, status, religion, a personal sense of security) all found a common point of reference and were able to be brought together under a larger and surprisingly comprehensive view of the world above and around them and their place in it.

Certainly, “very few people reflected in a systematic fashion—or at all—on how these different aspects of their lives were held together through the person of the emperor,” as indeed the “hallmark of any successful ideology … is its invisibility to those who live under it.”

What is special about John’s Gospel, now, according to Richey (50-51)?

It is only when one steps outside of a meaning-system, when, like Jesus, one “overcomes the world” (John 16:33), that it can become an object of reflection and criticism. When the Johannine community stepped outside of this ideology (and outside the legally privileged realm of the synagogue as well), it unavoidably placed itself against the Roman world in which it lived. It is to the results of this conflict, namely, the danger of persecution by Roman authorities experienced by the Johannine community, that we now turn.

↑ 2.2 Exclusion from the Synagogue and Persecution as Challenges to the Johannine Community

Recalling (51) that the “synagogue was a ‘legally privileged realm’ within Roman society” and “Jews in Roman society were exempt from many of the practices of the Augustan Ideology,” Richey again emphasizes how traumatic the loss of “this special status” must have been for the Johannine community, bringing them “at odds not only with the Jews but with Rome as well.” He therefore outlines “the dilemma facing Johannine Christians when the Gospel was composed: while no longer Jews either legally or theologically, neither were they Romans.”

Two points of view I consider questionable in this analysis:

First, it cannot be assumed that the Johannine community at the time of the writing of the Gospel already understood itself as Christian in contrast to the religion of Judaism. Ton Veerkamp assumes that it rather understood itself well Jewish as the true Israel trusting in the Messiah Jesus, while it reproached the Judean leadership at the time of Jesus for submitting to the Roman emperor as their only king (John 19:15), and also ultimately condemned Rabbinic Judaism as “children of diabolos” by coming to terms with the emperor as the “murderer of humans on principle” <30> and the Roman world order led by him.

Second, it can hardly be supposed that the Johannine community should have gained its critical insights into Augustan ideology, as mentioned by Richey, only after its exclusion from the synagogue. For every Jew, trust in the one God of Israel diametrically contradicted the deification of the Roman emperor, and even if Jews were exempt from the Imperial Cult, especially Messianic Jews, who expected from the Messiah Jesus the inception into a life of the coming world age of peace, had to perceive the presumption of the Roman world rulers to have established a Pax Romana in their militarily “pacifying” way as sheer mockery.

Unlike Richey, I would accordingly describe the Johannine community as Messianic Jews who are not Romans and at the same time have lost the legal protection of the synagogue led by Rabbinical Jews.

After all, even according to Richey himself (51-52),

it is very difficult to determine the exact status of the Johannine Christians with respect both to the Roman government and to the synagogue: in both contexts, their position was “extra-legal.” The Johannine community, in the eyes of the Romans, was not a legal entity but a vague association of people who could not be accurately numbered. Likewise, for those Johannine Christians who had been made aposynagōgos, the synagogue would no longer make official notice of them. Being neither Jew nor Roman, the Johannine community fell between the cracks in first-century society, leaving no records that would give us direct access to their legal and religious situation. Therefore, as with the reconstructed history of the Johannine community of J. Louis Martyn and Raymond E. Brown, our study here is necessarily inferential and our primary sources scanty.

↑ 2.2.1 „Socio-Legal“ Effects of the Imperial Cult on the Johannine Community

To determine the impact of Augustan Ideology on the Johannine community (52), Richey leaves aside

the auctoritas of the emperor and the “literary-mythic” aspects of the Augustan Ideology, not because they were unimportant—they were perhaps even more important than the Imperial Cult—but because they were by definition ideological and not obligatory in the strictest sense of the term. Only in the Imperial Cult do we find a legally constituted and manifestly public forum within which participation or non-participation could be easily recognized and punished.

At least for the first century, it is true that the “Imperial Cult relied far more upon social pressure rather than legal sanction for its success.” Such festive events apparently often resembled fairs (53) that served to sell goods, and “[b]ecause of its entertainment value, as much as for any religious content the Imperial Cult might have, encouragement to attend was probably unnecessary for many people.”

Moreover, as Fishwick [2. 1. 529] writes,

since “the different sections of the municipal populace would have been represented whenever or wherever the town paid cult to the emperor,” the absence of members of the Johannine community might have been noted by authorities.

Richey therefore suggests that “[c]omplete avoidance of these ceremonies would have been difficult anyway, if for no other reason than their scale and their place in the public calendar.”

As to the participation (54) of the individual “in the official rites performed by the high priest,” Richey writes, quoting Fishwick [2. 1. 529-530], that

in principle everyone was expected to take part but all that was required was to wear festive attire, notably crowns, and to hang the doors of one’s home with laurels and lamps. … Above all, formal participation did not, as a rule, impose any obligation to perform rites; individuals were free to pay cult or not as they chose. In practice it seems clear that everyone did join in, even the elite, to some of whom the emperor cult might appear laughable or offensive.

According to Alföldy [255],

“[i]n the cult of the emperor, however, practically everybody was involved. This is true in a double sense. Spatially, the ruler-cult was carried out at Rome as well as in all the towns of Italy and the provinces, and even in private houses. Socially, it was spread through all classes and groups.”

According to Richey, this leads to the conclusion (55):

Given the popularity of and broad demographic representation at the festivals, systematic avoidance of them would have been noticeable, to say the least.

More serious still, the “official” character of these ceremonies made any public resistance to them appear as anti-social and a potential threat to the public order deserving the notice of the Roman authorities.

Karl Christ [161] hence speaks of a “systematic merger of politics and religion” that “was characteristic of the new religious system” and due to which the “cult worship of the princeps became an act of political loyalty.” However, “willingness to perform sacrifice came to be used as a key test of Christians” only later, namely “during the persecutions” of the second and third centuries. <31>

It was (56) Richard Cassidy, <32> who

has argued that John 21 refers, in part at least, to public trials and political loyalty-tests similar to those imposed by Pliny a generation later. In John 21:18-19 Jesus says to Peter: “Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you girded yourself and walked where you would; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish to go. (This he said to show by what death he was to glorify God.)”

The “lesson of this passage,” according to Cassidy, applies to “all those charged with pastoral responsibility for the community.” From this Richey concludes

that at least the leaders of the Johannine community may have had a certain prominence that could attract Roman attention, or even perhaps a duty to place themselves in harm’s way for the good of the community.

It has been objected <33> that, “for Christians, then, sacrificing itself was at stake, not obeisance to the emperor.” In response to this (56-57), Richey argues that possibly

Christians “were happy to pray for the state but not to sacrifice for, let alone to, the emperor,” [but] failure to perform such sacrifices was still considered a de facto defiance of the emperor subject to severe punishment, even death. The importance of the Imperial Cult for integrating the far-flung empire of the first century and reinforcing the position of the emperor within this empire made it a central element in the Augustan Ideology. Through it, the ideas of the auctoritas of the emperor and the destiny of Rome were able to be disseminated throughout every level of Roman society in a form both recognizable and powerfully persuasive. Given this context, it is not surprising that rejection of the Imperial Cult was seen not as a private decision but as a public and political act of rebellion against Rome, or that its punishment took place within the context of the cult.

In this regard (57) Fishwick [2. 1. 577] recalls

“the martyrdom of Christians … in the context of games linked with imperial festivals or put on by imperial priests. It was in the amphitheater that condemned prisoners were decapitated, burned alive or exposed to the beasts, so the setting was appropriate for the punishment of those who refused to pay cult to the gods of Rome, one aspect of which was the cult of the emperor.” The most notorious persecutions took place, of course, in the second and third centuries. However, the Neronian persecution of Christians in Rome in 64 C.E. indicates what Christian communities potentially faced already in the first century. <34>

↑ 2.2.2 Legal Status of Johannine Jesus Followers under Roman Rule after Their Exclusion from the Synagogue