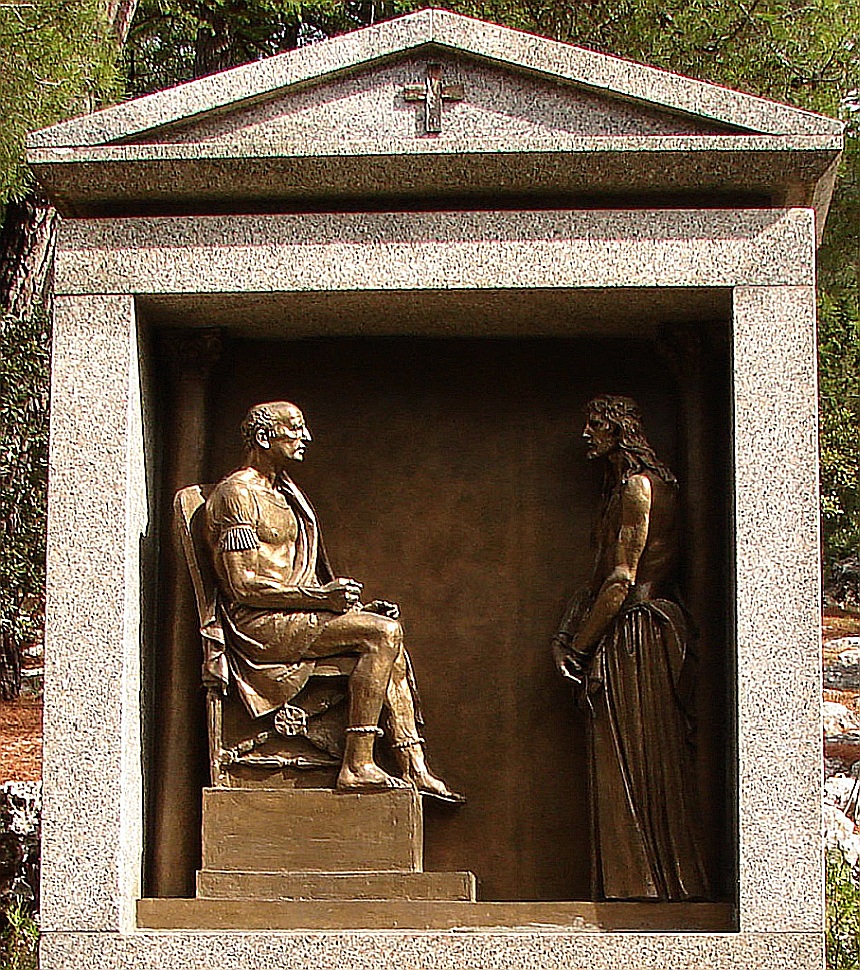

The world order, represented by Pilate, murders Jesus, the King of Israel. By voluntarily taking upon himself the death on the cross, the Messiah is ascending to the FATHER, thus handing over to his disciples GOD’s inspiration of fidelity. This Holy Spirit of solidarity is overcoming the world order.

The meaning of solidarity is signified by Jesus washing the feet of his disciples as a slave. As for overcoming the world order, he explains this to them in his farewell speeches and conversations. The events in front of and inside the praetorium show that the Roman world order is the real enemy of the Messiah, while the Judeans present here are standing for the part of the Judean people that has resigned itself to the Roman God-Emperor as the supreme ruler and is collaborating with Rome in order to get rid of the Messiah.

What Christians usually refer to as “Easter” is, in John’s Gospel, “day one,” which marks the beginning of a new creation and the victory of agapē (“solidarity”) over the “world order.” Paradoxically, the disciples nevertheless (at first) remain behind closed doors—for fear of the Judeans.

↑ {280} PART III: PASCHA—THE FAREWELL OF THE MESSIAH, 13:1-20:31

The third part tells the great Passover of the Messiah. The leaving of the Messiah is the new exodus of Israel. It has five passages, in our counting the passages 12-16, separated by indications of time:

12. Before the Passover, 13:1-30a

13. “It was night,” 13:30b-18:28a

14. The First Part of the Passion Narrative: Early in the Morning, 18:28b-19:13

15. The Second Part of the Passion Narrative: ˁErev Pascha, 19:14-42

16. Day One of the Shabbat Week, 20:1-31.

The center of the last part is the long section about what happened during the night. It is the night of the Messiah’s farewell from the Messianic community and the delivery of the Messiah into the hands of the enemy through the leadership of Judea. Passover is the great festival of liberation. The Gospel of John is the “Easter Gospel” par excellence. This festival is always “near,” from the beginning, 2:13.

On the main day of the festival itself, nothing happens; everything happens immediately before and after the festival. This day is the great and decisive gap. It shows that the theology of the Gospel of John is a theologia negativa. The “handing over of inspiration” is the essence of the farewell, 19:30. The acceptance of this farewell is the “acceptance of inspiration,” 20:22. It enables the Messianic community to live a Messianic life without the Messiah.

↑ 12. Before the Passover, 13:1-30a

Now we have reached the immediate vicinity of the Passover festival, the eve of paraskeuē, the preparation day for the Passover festival, which the Jews call ˁerev pascha.

The time before ˁerev pascha is divided into three sections: the time of the last supper (13:1-30a), the night (13:30b-18:28a), and the early morning (18:28b-19:13). You {281} can see that the sections of the night are the main focus. This center is framed by two shorter pieces: The Meal and Early Morning in front of the residence of the Roman authorities. The first piece shows that the Messiah is called Lord, but is the slave. The second piece of the frame clearly shows that the Messiah is King, but a completely different King than all the others before him and after him. Only as a slave, the Messiah is King.

During the long night between evening and early morning, Jesus will try to explain the essence of his Messianity and the consequences for the disciples. We begin with the evening. The passage 13:1-30a can be divided well:

13:1-17 Lord and Teacher as a slave

13:18-30a Lord, who is it?

↑ 12.1. Lord and Teacher as a Slave, 13:1-17

13:1 But before (401) the festival of Pascha, (402)

in awareness (403)

that Jesus’ hour had come to pass from this world order to the FATHER,

being solidarized with his own under the world order, (404)

his solidarity with them came to its goal,

{282} 13:2 and after a meal was held, (405)

—after the adversary (406) had already set

the heart of Judas, son of Simon Iscariot, to hand him over—, (407)

13:3 in awareness then,

that the FATHER had given everything into his hands,

that he had come from GOD and went to God:

13:4 He gets up from the meal,

puts off his garments,

and taking a linen apron (408) girded himself.

13:5 Then he pours water into the basin,

began washing the feet of the disciples

and drying them with the apron that he had girded himself with.

13:6 He comes to Simon Peter, this one says to him,

“Lord,

You are washing my feet?”

13:7 Jesus answered, he said to him,

“What I am doing you do not understand yet,

you will recognize after this.”

13:8 Peter says to him,

“You will not wash my feet until the age to come!”

Jesus answered him,

“If I do not wash you, you have no share with me.” (409)

{283} 13:9 Simon Peter says to him,

“Lord, not only my feet but also my hands, my head.”

13:10 Says Jesus to him,

“He who has bathed needs nothing but to wash his feet,

he is clean, entirely.

You too are clean, but not all of you.”

13:11 For he knew of the one who would hand him over;

this is why he said, “Not all of you are clean.”

13:12 When he now had washed their feet,

taken his garments and reclined again to the table,

he said to them,

“Do you recognize what I have done to you?

13:13 You call me ‘Teacher’ or ‘Lord,’

you say that well because I am.

13:14 Now if I—the Lord and Teacher—wash your feet,

you ought to wash each other’s feet as well.

13:15 For I have given you an example: (410)

as I have done to you,

you shall do as well.

13:16 Amen, amen, I say to you:

The slave is not greater than his master,

the sent one no greater than the one who sent him.

13:17 If you are aware of this,

you will be happy if you do so.

The part begins with a monumental sentence, built over two bridge pillars, the two active participles eidōs, “in awareness,” and agapēsas, “in solidarity,” on the one hand, and the repetition of the participle eidōs, “in awareness,“ on the other.

In between are two so-called genitivi absoluti, a grammatical figure denoting accomplished facts: The meal is over, the enemy has taken possession of a disciple.

This sentence is a prefix, the main sentence begins in v.4, “he gets up from the meal . . .”

The prefix contains in a very concentrated form all the themes that will be discussed in 13:1-17: the awareness and solidarity of Jesus. Both determine the action to come. Jesus, the Lord and Teacher, acts as a slave so that no one among them can {284} become Lord: this is solidarity. That it is solidarity is not named until after the break of the betrayal: the words agapē and agapan, “solidarity” and “to solidarize,” we hear first in the great prefix about the awareness of Jesus and then again in 13:34, in the night.

Jesus’ awareness contains four moments: Jesus knows that his hour has come to leave this world order to go to the FATHER, that his solidarity with his own has reached its telos, its “goal,” and, after mentioning two accomplished facts, Jesus knows that all power has been given to him because his whole life is “moving from God to God.” These four moments: the hour, the goal, the power, and the way, summarize the first twelve chapters of our text. It is from this knowledge that Jesus is acting.

The first genitivus absolutus: “when the meal was over.” So the decisive thing happens after the meal. The meal that is held here is not the Passover meal. The word deipnon, “meal,” occurs four times in John, once in 12:2-3, where Mariam anointed the feet of the Messiah, twice here and then again in Galilee, on the shore of the lake, 21:20, but where reference is made to this meal here.

So there are only two meals, the first was the anticipated funeral meal where Lazarus was present, Martha did the Messianic honor service, and Mariam “anointed the Lord with balm and dried His feet with her hair“ (11:2 and 12:3 ff.), six days before Passover (“Monday”); the second meal was one day before ˁerev pascha (“Thursday”). Does the deipnou genomenou refer to the first meal?

The second meal is linked to the first meal. After the meal, where Mariam anointed the feet of the Messiah, Judas ben Simon Iscariot will bring the poor into play to discredit the anointing. After this meal was done, Simon Peter sought to prevent the action of Jesus on the disciples, the washing of feet, and Judas is asked to leave Jesus and the disciples. Again, the needy are mentioned (ptōchoi). After the first meal, the death and burial of the Messiah are anticipated; after the second meal, the new commandment of solidarity is established. After the first meal, it is made clear that now was not the hour of the needy; after the second meal, the new commandment of solidarity among the disciples is proclaimed.

The second genitivus absolutus, “After the adversary had put Judas ben Simon Iscariot in his heart to hand him (Jesus) over.” Judas acts on behalf of the adversary, satan, diabolos, not of an evil supernatural spirit, but an evil inner-worldly order. He acts on behalf of and as a henchman of Rome, we see him here, we see him going away (13:30), we see him again as the head of a mixed force of police of the Judean authority and soldiers of the enemy, 18:3. When the Scriptures use the word satan, it does not mean demons; for these, it has other words. We recall here what we said at the discussion of 6:70 and 8:44.

Once again, Jesus’ awareness is emphasized before he is washing the feet of the disciples. He knows that he is the one to whom all power has been transferred, like the bar enosh, the Human. He has gone out from God, he returns to him, in this awareness {285} he takes off his garments and takes an apron, the clothing of a house slave. The act of washing the feet of the guests at a banquet was an obligation of the house slaves. Jesus takes over this role, to the horror of the disciple Simon Peter.

Why he? Were the others not horrified? Of course, because even a slave of Israelite origin is not obliged to wash the feet of his master. (411) Jesus acts like Abigail who said to David, 1 Samuel 25:41, “There is your handmaid as a slave to wash the feet of my master’s slaves.” Jesus is acting like the slave woman Abigail. The horror of Simon is emphasized because he embodies the leadership of the Messianists. John deliberately gives Simon the role of resisting the request of Jesus. Jesus knows that if he does not persuade Simon to submit to this act of Jesus, his future role as “shepherd” and so the whole is at stake; otherwise, Simon (the Messianic movement) would have no part in him.

Simon’s desire that Jesus should wash his hands and his head is strange, for the Scriptures never speak of washing the head but of washing the hands; the latter is in any case related to the commandment of purity. Jesus should wash those parts of his body that are not covered by clothing, that is, feet, hands, and head.

Jesus takes this up by using the word “to bathe.” He who has bathed is pure. They have bathed, they have gone through the immersion of the words of the Messiah. The suggestion of Simon is therefore absurd; he has bathed, his feet, hands, and head are “bathed.” The washing that Jesus performs here is not for purification. Only one is unclean, the henchman of Rome.

Foot washing is about something else. That is what Jesus must explain. The disciples relate to Jesus, to the Lord and Teacher, just as the disciples of a rabbi relate to the rabbi. Jesus could claim this role for himself in this circle, eimi gar, “for I am,” namely Lord and Teacher. But he is the slave (doulos, ˁeved).

The conclusion is not a religious one, such as, “Because God (the Messiah) loves men and serves them, they shall love God (the Messiah) and serve him.” On the contrary, if the one “like-God” (hyios theou) makes himself a slave (doulos) of these humans, these humans must be slaves to one another: from the vertical (“I for you”) follows the horizontal (“you for one another”); in the language of Bonhoeffer this would mean “pro-existence.” The relationship of God to the Messiah and of the Messiah to the disciples is strictly exemplary, “As God to me, as I to you, so you to one another.” In John, there is no universal love of neighbor, and in him, there is certainly no religion. (412)

↑ {286} 12.2. “Lord, who is it?”, 13:18-30a

13:18 Not about all of you do I am speaking;

I know which ones I have chosen,

but that the Scriptures may be fulfilled:

The one chewing (413) my bread

lifts up his heel against me. (414)

13:19 From now on, I am speaking to you before it happens,

so that when it does happen,

you may trust that I AM—I WILL BE THERE.

13:20 Amen, amen, I say to you:

He who receives someone I send receives me;

He who receives me receives the ONE who sent me.”13:21 When saying this, Jesus was totally shaken, (415)

he testified and said,

“Amen, amen, I say to you:

one of you will hand me over.”

13:22 The disciples looked at one another,

puzzling over who he is speaking about.

13:23 One of his disciples was reclining,

borne by Jesus in his bosom,

the one Jesus was attached to in solidarity. (416)

13:24 To this Simon Peter motions

to inquire who it is he is speaking about.

13:25 Leaning now against Jesus’ chest, (417) that one says to him,

“Lord, who is it?”

13:26 Jesus answers,

“It is the one to whom I will dip the bite and give it.”

Having dipped the bite, he gives it to Judas ben Simon Iscariot.

{287} 13:27 And after the bite, the adversary went into him.

So Jesus says to him,

“What you are doing, do quickly.”

13:28 None of those who were reclining at the table recognized,

to what end he said that to him.

13:29 For some thought,

that since Judas had the money-bag, Jesus would have said to him,

“Buy what we need for the festival,”

or that he give something to the needy.

13:30a So that one took the bite and went out, immediately.

After this exemplary act of Jesus, there is the dissonant counterpoint, “Not about all of you do I speak.” The text does not linger long with psychological attempts at explanation. Judas is the evildoer of the Psalms, and he is the one who commits crimes against the people. The “I” of the Psalms always stands for Israel too.

Even the man of my peace,

on whom I relied,

who ate my bread,

attacks me from behind.

So it says in Psalm 41 (v.10). John has his own Greek version of the psalm. Instead of “eating” (ˀakhal, esthiein) he has “chewing, gnawing” (trogein) as in the bread speech 6:54 ff. The parallel is intentional: Judas was the one who chewed the flesh of the Messiah, that is, he was one of those who did not go away despite the scandalous sayings of the Messiah in the bread speech. It does not mean, then, that he took part in a Christian communion and then betrayed the Messiah; it means that he was fully engaged with the Messiah (chewing his flesh, drinking his blood). It is he who hands the Messiah over to the Romans and their collaborators, Judas ben Simon Iscariot, who once was chewing the flesh of the Messiah, drinking his blood.

Psalm 41 ends with a double Amen, “Bless the NAME / the God of Israel / from ages to ages / Amen and amen!” After Jesus announces what will happen before it happens, “so that you may know: I WILL BE THERE,” he takes up the double Amen: “Amen, amen, I say to you.” Here again, the dialectic of the vertical and the horizontal, “Whoever accepts someone whom I will send (a Messianically inspired person) accepts me, the Messiah.”

John then leads the break in the narrative over foot washing and solidarity in a ghostly scene to a climax or an absolute low point. This narrative of the break leads from the shaking of Jesus (etarachthē tō pneumati) in v.21 to “it was night, however,” in v.30b. It begins with the double Amen of Psalm 41:14, this time turned into darkness, “Amen, amen, I say to you: one of you will hand me over.” The four acting persons are Jesus, Simon Peter, the apprentice “to whom Jesus was attached in solidarity,” and Judas ben Simon Iscariot. Jesus’ shaking is the same as the one in the face {288} of the death of Lazarus. He prays the Psalm of the Shock (6:4) in 12:27, “Now my soul is shaken.” The Messiah is completely and deeply shaken (tō pneumati) in the face of the corruption, the inner decay, prevailing in this people. Lazaros was the decaying Israel, Judas ben Simon Iscariot the son of his people, eaten up by corruption.

We do not want to add our own speculation about the disciple with whom Jesus was friends. The text passes him on anonymously, and we should respect that. In any case, here begins the strange alliance between Simon Peter and the so-called beloved disciple. The disciple to whom Jesus was united in solidarity (ēgapa) or in friendship (ephilei) is not necessarily identical to Lazaros, who was also in friendship with Jesus (hon phileis, 11:3). He is the disciple who walked the whole way with Jesus, from the garden to the court of the great priest, from the court to the cross, from the cross to the open tomb, from this tomb to the fishing boat, from where he was the only one who recognized the stranger as “the Lord.” He is the exemplary disciple who will always remain until the Messiah comes, 21:22. He is the structural transformation of Lazarus. This one was the exemplary concentration of the dead and to be revived Israel, the disciple in the Gospel of John is the exemplary concentration of living Israel, the Jewish—not Christian!—Messianic community.

At the level of the narrative, the traitor remains unknown; Jesus knows, perhaps that anonymous disciple knows, all the others will know only when they see him again in the garden beyond the brook Kidron. Jesus hints at it, but in such a way that nobody recognizes who is meant. Jesus gives the dipped bite to Judas, and the disciples assume that it is aimed at the story of Ruth and not at Psalm 41. Here the passages of the Scriptures, Psalm 41:10 and Ruth 2:14, are fulfilled. The second passage is turned into its opposite so that it can point to the first.

This is exactly the instant when the adversary “entered,” a truly “Satanic” reversal of the gesture of Jesus, distinguishing Judas ben Simon as a housemate. So says the Scripture passage Ruth 2:14. Ruth came as a refugee from Moab to Boaz, the owner of a farm in Bethlehem, and asked for permission to gather barley after the harvest. Boaz said to Ruth at mealtime,

“Come closer; you may eat from the bread,

dip your bite into the sour dip.”

She sat down beside the reapers,

and he handed her roasted grain.

She ate, was satisfied, had some left over.

Thus Ruth was accepted by Boaz as a housemate. By accepting the dipped bite, Judas accepts recognition as a fellow housemate of the Messiah and deceives those present. He hides from those present by accepting recognition as a housemate that he will hand over Jesus. He accepts the role that Rome—the Satan—assigns him.

Jesus wants this theater to end quickly, “What you are to do”—namely, to carry out the assignment of the adversary, Rome—“do it quickly.” John keeps up the tension {289} by having the disciples puzzle; they suspect nothing of what is really going on. “Immediately (euthys) he went out.” It is the first time we hear the word euthys in John. Twice more we will hear this word. Judas knows that the hour of Judas has come at the same time as the hour of Jesus: He could no longer remain in the “house of the Lord.”

↑ 13. “It was night,” 13:30b-18:28a

↑ 13.1. The New Commandment, 13:30b-38

13:30b It was night, however. (418)

13:31 And when he had gone out, Jesus says,

“Now the bar enosh, the Human, began being honored,

and GOD began being honored with him.

13:32 If GOD began being honored with him,

GOD will also honor him with himself, (419)

and, immediately, he will honor him. (420)

13:33 Children, still a little while (421) I am with you.

You will seek me,

but, as I said to the Judeans,

where I am going, you cannot come,

so I say it to you now.

13:34 A new command I am giving to you:

that you are solidary with each other,

that—just as I was solidary with you—

you are also solidary with each other.

13:35 By this, everyone will recognize that you are my disciples,

if you are practicing solidarity with each other.

13:36 Simon Peter says to him,

“Lord, where are you going?”

Jesus answered,

{290} “Where I am going, you cannot follow me now;

you will follow later.”

13:37 Peter says to him,

“Lord, why can’t I follow you now?

I will put in my soul for you!” (422)

13:38 Jesus answered,

“You will put in your soul for me?

Amen, amen, I say to you:

The rooster will not call until you have denied me three times!

“It was night, however.” Now the night of the Messiah begins. The reading of our text up to this point has shown what night meant; it is the time without the Messiah, in which you cannot walk the way, but you must “stumble” (11:10), in which “no one can work,” 9:4. The night of Rome without the Messiah is the end of all hopes and all plans. But this night is the night of the Messiah.

John tries to make it clear to the group that the Messianic community also lives in the night. It must learn to decide whether its night is the night of the Messiah—a night in which the Messianic light shines upon it—or whether its night is the night of Rome—then it really can do nothing. How is it possible to live in the Messianic night without the Messiah? John seeks an answer to this question in the so-called farewell speeches.

The word “honor” (doxa, kavod, gloria) becomes increasingly important in the course of the Gospel. From Chapter 11, the revival of Lazarus, to Chapter 17, the prayer of the Messiah, that doxa, “honor,” is a main theme. The glory of God is not like the quickly offended glory of men. The honor, kavod, actually “force, brunt,” is his assertiveness in the realization of his “project” Israel.

At the revival of Lazarus we heard how sickness and death serve to “honor the one who is like God,” and Martha’s despair is met with the word, “If you trust, you will see the honor of God.“ What is happening at the tomb of Lazarus means that “the honor of God” is that Israel is alive.

Whenever Jesus’ shaking is reported (11:33; 12:27; 13:21), the “honor of God” comes into play. The Messiah prays, “FATHER, honor your name.” The “voice from heaven” declares, “I have honored it, and I will honor it again,” 12:28. And here, after the shaking experience that one of the Twelve betrays the Messiah, Jesus says: “Now the bar enosh, the Human will be honored; with him, God will be honored . . ., and God will also honor him with himself, and immediately (euthys) he will honor him.”

{291} We know what the honor, the power of God is: that Israel lives. This happens at the moment when the apparent doom is introduced by the betrayal: The Messiah is murdered, Israel lives! This is realized immediately, at that very moment when Judas ben Simon enters the ranks of the enemy. We can understand this only when we hear the word euthys a third and last time, 19:34.

What happens here is unique; the attempt to imitate the Messiah is an illusion, “Where I am going, you cannot come,” he said to the Judeans (7:34), and he has to tell this to the disciples as well. Thus the question of Simon Peter is anticipated and, at first, answered negatively. Positively, the place is shown to him where he can and must go. This place is solidarity, the new commandment. The washing of feet is the sign of the new commandment. Here Bultmann is right,

There is no love directed directly at Jesus . . . as there is no love directed directly to God (1 John 4:20-21). Jesus’ love is not a personal affection, but rather a liberating service; its response is not a mythical or pietistic Christ-intimacy, but the allēlous agapan.” (423)

This inner solidarity of a political underground group seemed so urgent to John that he, the Judean, repealed Deuteronomy 6:5, “You shall love the NAME, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your passion.” It says, for the Rabbinical Judeans as well as for the Messianists, “Where I am going, you cannot come.” God—to whom the Messiah goes—is inaccessible to men. This is a basic insight of the Scriptures, “The human cannot see ME and live,” Exodus 33:20. But according to Rabbinical Judaism, “love” for God is not only a possibility but an unconditional obligation of Israel. In John, there is the solidarity (“love”) of God and the Messiah with humans, but not vice versa. For humans only solidarity among themselves is possible—but then this is an unconditional obligation as well. Solidarity with (“love” for) the Messiah is to follow his commandment, we will hear this emphatically, 15:1 ff. In this way and only in this way God is honored. No double commandment in John.

The question after the defeat of the year 70 is: What is the point of a messianic vision? The crushing defeat in the year 70 meant the end of messianism for many messianists. To Rabbinical Judaism, messianism should no longer be a political priority for the time being. To the group around John, this is the real challenge. If the Messiah is not on the agenda, what is this group still doing among the children of Israel?

The Messiah goes to a place that is inaccessible to all, “Jews” or “Christians.” Even Simon Peter cannot follow him, “later you will follow,” is the enigmatic answer to Simon’s question in this regard. Only in chapter 21 will this become clearer: Simon Peter will have to go through the same defeat through which the Messiah likewise goes.

{292} Simon-Peter conjures to Jesus his readiness for the messianic jihad, his Zealotism, because that means tithesthai tēn psychēn, “to put in his soul.” Jesus rejects the request of Simon by announcing his denial. This expression “to put in one’s soul” does have a vertical dimension: the Messiah as the shepherd puts in his soul for his sheep, because he has received authority to do so (10:18). From this vertical dimension, however, only a horizontal dimension results for the disciples (see 1 John 3:16); you can put in your soul for the brothers, but not for the Messiah, let alone for God.

In the garden beyond the brook Kidron, Simon will try to follow the Messiah in his own way, with the sword drawn. In the courtyard of the great priest, Simon will do the obvious: he will deny Jesus; he will understand that there is no chance with the drawn sword, he will finally and politically understand the Messiah.

The Messiah does not value the denial; he only notes that Simon, faced with the choice in the courtyard of the great priest, cannot follow the Messiah at this moment. He will have to “deny” him, i.e., do the opposite of what John four times calls homologein (“to confess, to admit”) (1:20 (twice); 9:22; 12:42).

The point of Simon’s words here is the call for a new heroic or Zealotic adventure. “Why can’t I follow you now? I will put in my soul for you,” means, “Why don’t we fight? Let us fight the Romans for a new Messianic world order.” Such succession would be the march to ruin—and was the march to ruin in the years 70 and 135.

↑ 13.2. Three Objections, 14:1-14:26

↑ 13.2.1. The First Objection: “We don’t know where you are going,” 14:1-7

14:1 Your heart shall not be shaken. (424)

Trust in GOD and trust in me.

14:2 In my FATHER’s house, there is for many a place of permanence. (425)

If not, would I have told you

that I am going to found a place for you? (426)

{293} 14:3 And when I have gone and founded a place for you,

again I am coming to accept you to myself, (427)

so that where I AM, you may be also.

14:4 And where I am going—you know the way.”

14:5 Thomas says to him,

“Lord, we do not know where you are going.

So how can we know the way?”

14:6 Jesus says to him,

“I AM—the way and the fidelity and the life.

No one is coming to the FATHER except through me. (428)

14:7 If you have recognized me,

then you will also recognize my FATHER.

And from now on, you recognize him and have seen him.”

Of course, they are shaken. How can they not be shaken by the catastrophe of the year 70? Jesus says he is going so that the disciples will be there where Jesus will be there. Therefore their souls shall not be shaken, as the soul of the Messiah was shaken in the face of the friend’s death, 11:33, and he admitted this before the crowd, 12:27. Now he does not want to pray Psalm 6:4, “My soul is shaken.” Rather, defeat will be the turning point. The cross is his exaltation, and the exaltation is the turning point; he will draw all to himself. So we heard it in 12:27-33.

Now Jesus goes into detail: he will “found a place.” Very soon, these words were understood to mean that Jesus will establish a permanent dwelling place beyond this earth and this life for those who believe in him. This is a putting off to a hereafter that John did not know at all. Nevertheless, in his eyes, the real-earthly perspective of zōē aiōnios, the life of the coming world age, moves into a far distance. Although “heaven” is for John the realm from which the bar enosh, the Human, comes and to {294} which he returns, nowhere is heaven a perspective for humans. We cannot understand the text if we are guided by a widespread (early) Christian transcendence. Jesus does not search for heavenly homes for the disciples. The monē is a permanent residence on earth, “residence for many.” The house of the FATHER is not heaven. (429)

In need of interpretation is the difficult sentence, “Again I am coming to accept you to myself.” The statement of this sentence is determined by the following final sentence, “so that where I am you may be also.” In Matthew, the matter is clear: the bar enosh, Human, is coming on the clouds of heaven to judge the living and the dead, the acquitted come “into the kingdom prepared for them, basileian hētoimasmenēn,” 25:34. John says something else. In his case, too, something is “prepared” (hetoimazein), instead of the kingdom, in John it is the place. John does not have a final trial (final judgment). Whoever does not trust the Messiah Jesus is already condemned, he is lost, he has no more perspective. For such a person only comes what is already there anyway: the death order of Rome.

Nevertheless, there is a tension between going and coming again. This tension is intensified in 20:17 by the word “not yet.” The place is without any doubt that synagogue into which Jesus will bring all of Israel together. This is the place of Jesus, where the disciples will be. In John, in the whole Scriptures in general, it is not heaven but the earth that houses the place to come (see Psalm 115:16).

In the conversation with the Samaritan woman, there was mention of the time when one is “inspired to the FATHER (NAME) and bows to him in fidelity” (4:23), but not of the place, or rather of the non-place: neither in Jerusalem nor on this mountain (Gerizim).

But here it is about the place and not about the time. In the conversation after the expulsion of the merchants and money-changers from the sanctuary, there is mention of the breaking down of the sanctuary and its erection after three days (2:19), but John says explicitly that Jesus means the sanctuary of his body. The place, ho topos, ha-maqom, is the sanctuary. To John, the place is the sanctuary, which is erected after three days, the body of the Messiah (sōma Christou, see Ephesians 4:12), the Messianic community.

But the “coming” is not only the establishment of the body of the Messiah, the Messianic community. By the word “rather,” palin, there remains an open space. Rather, a Jew hears in the word “place” the political earthly center of Israel. The coming of the Messiah has as its goal (11:52) the reunion of the God-born who have been scattered apart, and for this purpose an earthly place is necessary. Under the real Roman conditions, the Messianic community is a temporary place. The Messianic com{295}munity keeps the earthly, place-bound future of the Messiah open for Israel. We will have to go into this “coming” again in the discussion of 21:22. (430)

What is coming is the inspiration of sanctification. It can only come if the Messiah goes, “Where I am going: You know the way.” Thomas immediately teaches him better. “We don’t know where you’re going, how can we know the way?” Thomas—focused on the real political power balances—doubts that there can be a Messianic strategy. He said, “Let us also go with him, that we may die with him,” 11:16. Thus not, like Simon, “let us fight.” Jesus’ answer does not convince Thomas, “If I cannot physically convince myself of the future of the Messiah, I will not get involved,” says Thomas, as 20:25 can be paraphrased. The words handed down are not suitable for a psychological profile of the historical Thomas, but are sufficient for the political attitude he has to represent here: Under Roman conditions, there is no perspective anywhere.

Jesus answers in a saying that is one of the most quoted in the Gospel of John. In the traditional translation, “I am the way, the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father except through me.” By this saying, the absolute claim of Christianity is justified.

We have translated differently, “I AM—the way and the fidelity and the life.” This translation [fully capitalized “I AM” and breathing space indicated by a dash] first of all suggests that the statement is not a declarative clause, “I am the way . . .” The subject of the sentence is the Messiah. The definition of the Messiah is “the one sent by the FATHER (NAME).”

The definition of Moses was also “the one sent” of the NAME: ˀEhye sends me, the NAME sends me, Exodus 3:14. But the unity of the sent Messiah with the sender—the NAME/FATHER—has a different quality to John. Moses has spoken about way and life. In Deuteronomy 30:15-16, it says,

Look,

I have given you today:

life and good,

death and evil.

As I command you today,

to love the NAME, your God

to walk on his way,

{296} to keep the commandments, the laws, the legal regulations,

and you will live,

you will be many,

the NAME, your God, will bless you,

in the land where you come to inherit it.

Here, “way” and “life” are in clear relation to the “NAME.” In the song “Listen, oh heavens,” it says of the God of Israel, Deuteronomy 32:4,

The rock, perfect his work,

all his ways are just,

a God of fidelity, without deceit,

a trustee is he, straight ahead.

The God of Israel is “way, fidelity, and life” for Israel. Jesus is the way of God for Israel, he embodies the fidelity of God and is, therefore, the life for Israel. As the NAME happened by sending Moses—and Moses is the Torah—so the NAME happens today through the Messiah Jesus, 1:17. Moses proclaimed the way, fidelity, and life that God is for Israel. Now, Jesus is the only embodiment of the way of God, the fidelity of God, and the life that God promises.

Here is a contrast, but Christianity has turned it into an antagonistic contradiction: Moses or Jesus. The contradiction is not absolute, but conditional. It is the new conditions that suspend the old conditions and ask new questions. They demand a new answer: this is the basic view of all Messianic groups of all tendencies. Without this new answer, nobody comes to the FATHER.

To “come to the FATHER” means to walk in his ways, to act according to his commandments. Under the new conditions, it means, to walk in the ways of the Messiah, to act according to his new commandment. He who knows this new answer, the Messiah, this Messiah, is recognizing God. “From now on, you recognize him, and you have seen him.” There seems to be a contradiction here, “No one has ever seen God,” says John 1:18 (1 John 4:12), following the word Exodus 33:20, “No human sees me and lives.” This remains unchallenged and undeniable for him. And now, all at once, “You have seen him!”

↑ 13.2.2. The Second Objection: “Show us the FATHER, and it is enough,” 14:8-21

14:8 Philipp says to him,

“Lord, show us the Father, and it is enough for us.”

14:9 Jesus says to him,

“This long time I am with you,

and you have not recognized me, Philipp?

Whoever has seen me has seen the Father.

How can you say,

‘Show us the Father’?

{297} 14:10 Are you not trusting

that I am with the FATHER, and the FATHER is with me?

The words that I am saying to you, I am not speaking from myself.

The FATHER, permanently united with me,

is doing his works.

14:11 Trust me, that I am with the FATHER and the FATHER with me.

But if not, then trust because of HIS works. (431)

14:12 Amen, amen, I say to you,

the one trusting in me will do the works I do,

and even greater ones he will do,

because I am going to the FATHER.

14:13 Whatever you will ask for (432) in my name, (433)

I will do,

so that the FATHER may be honored with the Son.

14:14 If you ask me for something in my name,

I will do it.

14:15 If you are in solidarity with me,

you will keep my commandments.

14:16 I will ask the FATHER,

and he will give you another advocate, (434)

to be with you until the age to come,

{298} 14:17 the inspiration of fidelity (435)

which the world order cannot accept,

because it is neither observing nor recognizing it.

You are recognizing it,

because with you, it is staying continuously,

with you, it will be there.

14:18 I will not leave you as orphans,

I am coming to you.

14:19 Still a little while, and the world order no longer is observing me,

but you are observing me,

for I am living and you are going to live.

14:20 On that day you will recognize

that I am with my FATHER,

and you with me, and I with you.

14:21 Whoever has my commandments and keeps them,

that one is in solidarity with me.

Who is in solidarity with me,

he will experience solidarity through my FATHER,

I will be in solidarity with him,

I will prove myself real to him. (436)

Philipp takes this up immediately, “Show us the FATHER, and it is enough for us.” Apparently, there were doubters and skeptics in the group who almost drove “John” to despair. But just as obviously he takes this fraction very seriously.

{299} Their skepticism is justified, but it paralyzes the group in its struggle for a political perspective. In Jesus’ reply, this despair resounds unmistakably about those who say, “I want security.” Like this: we would be in this phase and that phase, it would take so and so long until the whole realm of death would collapse at its inner contradictions, and then . . . what comes then? The Messiah? These people must see that the God of Israel is faithful to Israel only by smashing unreal messianic expectations at the cross of shame of Rome.

So, unlike the Synoptic Gospels, John does not have the Messiah on the cross pray the 22nd Psalm, “My God, my God, why do you forsake me?” Not for a single moment was the abandonment of God a reality in the life of this Messiah. This is the main content of the message—from the beginning. Philipp was present from the beginning (1:43), and Philipp was an important figure in this narrative (1:43 ff.; 6:5, 7; 12:21-22). “So long have I been with you, and you have not recognized me, Philipp?”

He who sees the Messiah sees God, he who trusts the Messiah trusts in God. No other and no legitimate experience of God (“seeing”) is possible than seeing the Messiah, this Messiah, this failed Messiah! This seeing and recognizing is a practice. The practice of the disciples, if they see, recognize, trust, is that of the Messiah, and this practice will be more convincing than that of the Messiah himself (“greater works”). This Messianic practice is the honor of God, it and only it.

If you pray for it, it will be given, because praying for this practice requires seeing, recognizing, and trusting. The practice that arises from solidarity with the Messiah is the keeping of the Messiah’s commandments. In 15:12, it is again made clear what was demonstrated in Chapter 13: Solidarity with the Messiah = solidarity with one another = serving as slaves of one to the other disciple, of the other to the one disciple.

Instantly, it seems, sentences appear which refer to the prayer of the community. But the question is whether it is about “prayer.” For “prayer” the Scriptures have another word, hithpalel or proseuchesthai. If Jesus addresses the God of Israel (FATHER), then John uses a different word than if the disciples (should) do so. The Messiah “asks” (erōtan) for another “advocate,” that is, he will “request” him. The disciples “ask for” (aitein), and the utterance of this plea is in connection with the keeping of the commandments, here and in 15:7 and 15:16. This is not about rewards that the disciples would have earned by keeping the words or commandments of the Messiah. Rather, the point is that they then ask for exactly what meets the commandment of solidarity and the being with the Messiah. But this proves to be extremely problematic and is discussed in detail in the passage 16:23-28.

What comes now has given rise to a wealth of speculation as well as useless and therefore unscientific discussions: Who is the figure that John calls paraklētos, the Paraclete? We translate “advocate” according to his function in the court (16:7 ff.).

The word can mean “comforter” because it comes from parakalein; this verb originally meant “to summon” and in a derivative sense “to comfort, to encourage.“ It {300} derives from the Hebrew root nacham. In this sense, it is often used in the apostolic and evangelical writings, as is the related word paraklēsis, “comfort, encouragement.” The word group is missing in John, except for the word paraklētos, which in turn is missing in all other writings of both testaments. The word is found only in John and only if the world order is spoken of.

And John explains it: It is “the inspiration of fidelity,” which “the world order cannot accept or adopt.” One—the inspiration of fidelity—excludes the other—the world order of deceit—because the latter neither considers nor recognizes the former (fidelity is not an element of politics, not until today), and recognizing is to act following knowledge in the Scriptures.

Whatever or whoever the “Paraclete” might be, it or he is, in any case, the absolute contradiction to what is common practice in the world order of Rome. That is why this inspiration stays continuously with the disciples. Paraclete is what makes fidelity the center of all political practice. You don’t have to picture it as a “figure”; in this tradition, imagination (“images”) is impossible. If you know that fidelity is downright an apolitical category to Rome (Pilate, “What is fidelity?” 18:38) and that paraklētos or pneuma has just fidelity (alētheia) as its essence, then you know enough. The advocate, the inspiration of fidelity, is given when the commandment of solidarity with the Messiah and with one another is kept. The place of solidarity, the Messianic community, is inspired by fidelity and is thus the counterdraft to the ruling world order.

A last element of the answer to Philipp is the estimation of the absence of the Messiah. It does not mean that the Messianic community is orphaned. To Rome, this absence means that the Messiah no longer plays a political role; Rome has executed him, and the problem is dealt with. To this day, problems are settled by force in the Roman manner. Still “a little” (mikron), and the world order will no longer consider the Messiah (theōrei), but the disciples will consider him. The word mikron, which already sounded in 13:33, will still prove to be a huge problem, 16:16 ff.

Here the disciples are assured, “I live and you will live.” To consider the Messiah means, “I with my FATHER, you with me, and I with you,” that is the recognition. The recognition is threefold,

He who keeps the commandments and keeps them,

it is he who is in solidarity with me. (1)

Who is in solidarity with me,

he will experience solidarity through my FATHER. (2)

Consequently:

And I will be in solidarity with him, (3)

I will prove myself real to him.

{301} The paraphrase for emphanizein is “to prove oneself real.” (437) The Messiah is real for those who trust him, are in solidarity with him, and keep his commandment; he determines the lives of those who trust him. Beautiful. But is this more than an imagination of the group, more than a hallucination of people who have maneuvered themselves into isolation? It doesn’t change the course of the world order. Nothing more or less than the reality of the Messiah and the sense of reality of the Messianic community is at stake.

↑ 13.2.3 The Third Objection: “Why are you real to us and not to the world order?”, 14:22-31

14:22 Judas—not the Iscariot—says to him,

“Lord, what has happened,

that you are about to make yourself known to us

but not to the world order?”

14:23 Jesus answered and said to him,

“If someone is in solidarity with me,

he will keep my word,

and my FATHER will be in solidarity with him;

to him, we will come.

We will make ourselves a place of permanence with him. (438)

14:24 He who is not in solidarity with me is not keeping my words.

And the word you are hearing is not mine

but of the ONE who sent me, the FATHER.

14:25 These things I have spoken to you while I am staying with you.

14:26 But the advocate, the inspiration of sanctification,

which the FATHER will send in my name,

he will teach you everything,

he will remind you of everything I have said to you.

14:27 Peace I leave with you, my peace I give you,

not as the world order gives, I give you. (439)

{302} May your heart not be shaken nor timid.

14:28 You heard that I said to you,

‘I am going and I am coming to you.’

If you were in solidarity with me,

you ought to be glad

that I am going to the FATHER,

because the FATHER is greater than I.

14:29 And now I have said it to you before it happens

so that when it does happen, you will trust.

14:30 Not much more will I speak to you,

for the ruler of the world order is coming. (440)

With me, he has no concern at all, (441)

14:31 however, that the world may know

that I am in solidarity with the FATHER,

that I am doing as the FATHER has commanded me.Get up! Let us leave from here!

The reality of the Messiah is the solidarity of the disciples. Judas non-Iscariot—the disciple, one of the Lord’s brothers (442)—understands this as a lack of sense of reality, “So why not real to the world order?” This objection corresponds to the request of the brothers of Jesus to publicly manifest himself as the Messiah, 7:4, “Show yourself to the world order (phanerōson seauton tō kosmō).” Then the problem would be solved. But the Messiah has answered with his hiddenness.

{303} This problem is extremely urgent in all Messianic circles. Since the Messiah does not prove to be the decisive reality toward Rome, the confession of Jesus ben Joseph as the Messiah of Israel is completely hollow and dangerous for Rabbinical Judaism. His disciples might be tempted to prove the reality of the Messiah to Rome with a weapon in their hand, through renewed military but completely hopeless adventures. Therefore this kind of messianism should be fought.

Jesus’ answer has two parts. First, the summary of the teaching, 14:23-26; then the alternative: what peace does Rome bring, what peace does the Messiah bring, 14:27-31?

The summary sharpens some things. Solidarity with the Messiah is the keeping of his commandments, and the commandments coincide with the one, new commandment. Then the God of Israel shows his solidarity with Israel (agapēsei); here, agapē is in substance congruent with ˀemeth, “fidelity.” This solidarity or fidelity is expressed in the fact that “we come to him and make ourselves with him a place of permanence (monē).” Here the announcement of 14:2 is specified, and it becomes finally clear that it is not a matter of a “dwelling in heaven.” The direction is, if you like, from top to bottom and not from bottom to top. We do not get into heaven; if at all, heaven comes to us.

God and the Messiah become real through his indwelling in the solidary human. (443) God and the Messiah become unreal if there is no solidarity. Thus Jesus explains the verb emphanizein to Judas, “to become real.”

This is the sum of what the Messiah said, “while he was staying with them.” This is the persistent “teaching of the Messiah,” (444) it must remain in living “memory,” and this is the work of that “advocate” who here takes on the shape of a teacher: Only the “inspiration of sanctification” can teach the disciples all that the Messiah has said.

For the advocate, paraklētos, advocatus, works from God as “inspiration of fidelity,” pneuma tēs alētheias, and works on people as “inspiration of/for holiness,” pneuma hagion. In the Scriptures, “holy” is following God, Leviticus 20:7-8, that is, not a religious category, but a category of political practice, the practical implementation of the Torah.

This inspiration means “to remind.” Without solidarity, there is no living memory of the Messiah, and without this living memory of the Messiah, there can be no solidarity in the long run. The Messianic reality, that which manifests itself as real, is the coherence of the group. There, and only there, is God, is the Messiah, real.

John’s view of reality is a very condensed one. You get the impression that Judas non-Iscariot, with his very legitimate question, gets fobbed off by a very shortened {304} answer. This will have far-reaching consequences in the history of Christianity during the modern age—especially in pietism. The life of the age to come will become the individual eternal life beyond earthly places and times. But in John, the indwelling of God in the Messianic community is not the inner experience of a small circle but also a challenge to the world order.

The second part of Jesus’ answer is the challenge and refers to the absolute contradiction between the pax Romana and the pax Messianica. Peace is a desire because almost never was peace, and what was considered as peace was shabby, “greasy” (Ezekiel 13:10, 16!) violence, on a large and small scale, Jeremiah 6:13-14,

From small to large,

as profit takers, they profit;

from prophet to priest:

all their activity is a lie.

Allegedly they heal the rift through the people

and recklessly, they say:

“Peace, peace!”

But there is no peace. (445)

But this is pax Messianica, Psalm 72,

God, give your right to the king,

your truthfulness to the king’s son.

He shall judge your people truthfully,

over your oppressed ones with justice.

Then the mountains bring peace to the people,

and the hills in truthfulness.

He shall create justice for the oppressed of the people,

liberate the needy,

crush the oppressor.

Awe for you remains as long as the sun,

and the moon, generation by generation.

He may descend like rain on the meadow,

like dew trickle to the earth:

in his days the true ones flourish

and peace increases until there is no more moon . . .

Peace, truth, and justice belong indissolubly together in this Grand Narrative. Where there is no justice for the oppressed, where the exploiter flourishes, there is no peace. Peace happens to a people to whom justice happens, and justice is liberation from the oppressor, liberation from need. This pax Messianica is meant.

{305} But where Rome appears, interferes in civil wars like the civil war of the Judeans in the province of Judea, there it does not heal a rift in the people, but it destroys a part of the people and grinds down the house of its God. Pax Romana is war by other means, but no peace. Such “healing” always leads to wars—until today!

Why they should rejoice that he is going away remains unanswered here. That the Father is greater than the Messiah is no great consolation, since the presence of the Messiah is supposed to be the proof of the faithfulness of the God of Israel. We must wait for the reasoning 16:5 ff.

The Messiah has to say all this before the hour of probation comes; it comes when the “ruler of the world order” comes. (446)

What the Messiah has to do here serves to make the world order recognize that nothing and no one can drive a wedge between the Messiah and the God of Israel; they are to recognize “that I am in solidarity with the FATHER.” He must give himself into the hands of this ruler (literally, because Pilate is the representative of this ruler, the priests call him “friend of Caesar,” 19:12). Jesus will testify before him that there can be no mediation between the pacification by Rome and the peace of the Messiah: Between Caesar and the Messiah, there is only the connection of nothing, “With me, he has nothing [no concern at all],” it says. There is no mediation, no third, just “nothing,” ouden. The contradiction is absolute.

The departure of the Messiah is the “commandment of the FATHER,” because, under the real circumstances created by Rome, defeat is the only possibility of victory. On the cross, the world order is put in the wrong once and for all. This is the final unmasking of Rome. Unmasking is not the victory that we actually want, but Rome is in any case no longer fate, and there is no longer any reason for resignation. “Get up, let’s leave from here,” says Jesus.

Is everything clear? Nothing is clear. Jesus has to explain everything again before they can really “leave from here.”

↑ 13.3. The Parable of the Vine. Solidarity, 15,1-17

15:1 “I am the faithful vine, (447)

and my FATHER is the vintner. (448)

{306} 15:2 Every branch (449) in me bearing no fruit he takes away,

and every one bearing fruit he cleanses, so that it may bear more fruit.

15:3 Already, you are clean because of the word which I have spoken to you.

15:4 Stay united with me, (450) as I with you. (451)

As the branch cannot bear fruit by itself,

if it does not stay united with the vine,

so you can’t if you do not stay united with me.

15:5 I am the vine, you are the branches.

The one staying united with me and I with him,

he is bearing much fruit. (452)

Apart from me, you can’t do anything.

15:6 If someone does not stay united with me,

he will be thrown out like a branch and dries up.

Such branches are gathered, thrown into the fire, and burned.

15:7 If you are staying united with me,

and my words stay firmly in you,

ask for whatever you want,

and it will happen for you.

15:8 By this, my Father is honored

that you bear much fruit

and become my disciples.

15:9 Just as the FATHER was in solidarity with me,

so I was in solidarity with you.

Stay firmly with my solidarity.

{307} 15:10 If you keep my commandments,

you will stay firmly with my solidarity,

as I have kept my FATHER’s commandments

and am staying firmly with HIS solidarity.

15:11 This I have spoken to you

so that my joy may be with you,

and your joy will be fulfilled.

15:12 This is my commandment:

that you are in solidarity with each other

as I was solidarizing with you.

15:13 No one has greater solidarity

than someone putting in his soul for his friends.

15:14 You are my friends

if you do what I command you.

15:15 I no longer call you slaves,

because a slave does not know what his master is doing.

You, I have called friends,

because everything I heard from my FATHER

I made known to you.

15:16 Not you did choose me,

but I chose you,

put you to go and bear fruit,

fruit that will last,

so that whatever you ask for from the FATHER in my name,

he may give you.

15:17 This is what I command you:

that you are in solidarity with each other.

Here the “farewell speech” was finished. Obviously, the passage John 13-14 did not dispel the concerns of the group. John 15-16 summarizes another (phase of) discussion in the group. At first, this is done in a long monologue, 15:1-16:15, but then John resumes the form of dialogue characteristic of him, 16:16-17:1a. The same themes from Chapters 13 and 14 are discussed again.

This discussion starts with a classic Israelite metaphor, the vine. Three texts are in the background of the first verses of this section, 1-7.

The first one is Isaiah 5:1 ff.,

I want to sing for my friend,

the chant of my friend’s vineyard.

My friend had a vineyard,

on a fatty slope.

{308} He dug it up, freed it from stones,

planted it with red vines (soreq, ampelos sorēch),

built a watchtower in the middle of it,

hit a wine press pit from him.

He hoped for a grape yield,

it carried only rotten fruit.

Then Jeremiah 2:21,

I myself have planted you as a red vine (soreq),

all faithful seed.

How you have transformed yourself to me,

wrong, foreign vine?

In the Greek version,

I myself have planted you,

fruit-bearing vine (ampelos), very faithful.

How have you turned to bitterness,

you, foreign vine (ampelos)?

Then the song “Shepherd of Israel, listen” (Psalm 80). In this song, Israel is compared to a vine that God brought up from Egypt into the land, “its root rooted in . . . its branches stretched out to the sea.” The keywords of our parable John 15:1-2 (ampelos, “vine,” and klēmata, “branches, flowering twigs”) are also found in this song. The theme of the song is the decline of Israel, which has become the prey of foreign peoples. The refrain of the song (four times, v.4, 8, 15, 20) reads,

God: let us return,

let your face shine,

we will be liberated.

The texts see Israel as a vineyard where the vines bear fruit: Israel’s hoped-for yield is the legal order of its God. But in fact, Israel is the foreign vine that bears no fruit, and if it does, then only beˀushim, “rotten fruit.” To the desires for the restoration of Israel, the Messiah answers, “I AM—the faithful vine.” In Psalm 80, of all places, there is talk of a ben ˀadam (the Hebrew form of the Aramaic bar enosh), v.18-19,

Let your hand be over the man of your right hand,

over the Human, you made strong for yourself.

Never again we want to turn away from you,

let us live, who are called by Your name.

This background makes us understand what is said in this parable. The Messiah of Israel is that bar enosh, Human, and so Israel itself, Daniel 7:27. He is the absolute opposite of that deceptive Israel, that “wrong, foreign vine.” To describe Israel as a collective, the metaphor “vine” is used. The vine is the Messiah, the members of the {309} group are the flowering branches, the grapes. They must be provided for so that the grapes bear fruit. This is not the work of the Messiah, but the vintner, the God of Israel.

The work of God is “to cleanse.” Through the word (logos, davar) of the Messiah the disciples are clean, 15:3, that is, through the word, the disciples “already” fulfill that condition of purity which has always been fulfilled for each member of the people to participate in the community.

This is based on the intense connection with the Messiah, “Stay firmly with me, as I with you.” (453) The Messianic vision is the basic condition for a truthful life. If you are not really confident that the prevailing conditions, namely the “world order,” are not unchangeable, but that “life in the age to come” (zōē aiōnios) is a real perspective for the life of people on earth, you cannot do anything: For “separated from me (chōris emou) you can do nothing.” Otherwise, all doing is useless, barren, unfruitful.

To stay united with the Messiah is to stay united with his spoken words (rhēmata). And if you are firmly united with the Messiah, every prayer will be heard—admittedly based on this union—because the words dictate, so to say, what is to be asked for. These words are—so we shall hear—commandments.

The second part of this section (vv.8-17) is structured according to strict logic. First, however, it is stated what “to honor God” means to John. “To be a disciple of this Messiah” and “to be fruitful” is the Johannine definition of a truthful life that is worth living. The basic figure is always: The Father is in solidarity with me, I with you, you with each other. So that this figure may become real, a basic condition is formulated, “If you keep my commandments, then you will stay firmly in my solidarity.” To keep the commandments is, therefore, the union with the Messiah and thus a condition for fertility. The Messiah’s solidarity with the God of Israel is the keeping of his commandments. Therefore, what is required of the disciples is strict imitatio Christi, following the Messiah.

Before we hear the exact content of the commandments, the sentence about joy resounds. Four times we hear in the Gospel, “Joy is fulfilled.” Once it is said by John, three times by the disciples. It is both the joy of the Messiah and about the Messiah being fulfilled (3:29; 15:11; 17:13). John says that the bridegroom’s friend “rejoices with joy” when he hears the bridegroom’s voice; “this my joy is therefore fulfilled: He must increase, I must decrease,” 3:29. Twice the joy of the Messiah is fulfilled in the disciples, 15:11 and 17:13; once the joy of the disciples is fulfilled like the joy of a woman who has given birth to her child, 16:24. In the parable of the vine and its interpretation, joy is fulfilled through fruitfulness in the work of solidarity. It is about the fruitfulness (the works!) of the Messiah himself, which becomes real in the disci{310}ples. In the case of John, fertility had to decrease so that the Messianic fruitfulness could be all the more evident. (454)

“This is my commandment: that you are in solidarity with each other.” For the group around John, which is going through a most difficult phase—the people are running away from it, 6:60 ff., they are quarreling and hereticizing each other, 1 John 2:18; 2 John 10; 3 John 9—the group’s coherence is vital. Solidarity is entirely focused on the group itself. As I said before, there is no trace of universal charity or philanthropy.

The move into sectarianism rubs off on Jesus himself: No one has greater solidarity than putting in his soul for his friends, he says, calling the disciples “friends” and no longer slaves. This should be compared with Romans 5:7 ff., where this commitment in its most extreme form—the giving of one’s life—is not for the sake of friends but for the sake of those who have gone astray! The friendship of this tiny circle with the Messiah is based on the fact that Jesus “made known to them what he had heard from his FATHER.” They are the preferred—and at first the only—addressees of this announcement.

John himself senses that despite all friendship the proportions must remain clear. Not the disciples chose the Messiah, but the Messiah chose the disciples, stating the purpose of this election, “To bear fruit = to be in solidarity with one another.” We will have to come back to the election at the discussion of 15:19. The friendship of the Messiah has the effect that he will obtain the answer of the FATHER to their prayer. Friendship is a gift of the Messiah; there is no legal title for it.

Once again we draw attention to the very narrowly defined area in which solidarity is effective. We can hardly imagine it. To us, the disciples are simply the placeholders for all Christians. Since Christianity has at times been presented as congruent with the whole of humankind, solidarity among the few friends becomes a general virtue. But this makes it impossible to understand our text correctly. We have called solidarity a combat term and interpreted it analogously to the solidarity in the labor movement of the 19th and 20th centuries. (455) In the sectarian milieu of the Gospel of John and the Letters of John, agapē was primarily an in-group virtue. Only when the sect broke through its isolation and John became a church text, did the Johannine solidarity become politically fruitful. Admittedly, in church use, solidarity, as a Messianic virtue par excellence, became general human love and thus lost its political power. It was once coherence in the fight against the world order of death. It became the general philanthropy sauce that was poured out over the world order of death. Such moralization is foreign to John.

↑ {311} 13.4. The Fight, 15:18-25

15:18 If the world order is fighting you with hatred

recognize that it has fought me as the first of you.

15:19 If you were of the world order

the world order would be friendly to its own.

Because you are not of the world order

but I have chosen you out of the world order,

therefore, the world order is fighting you with hatred.

15:20 Remember the word that I said you,

‘A slave is not greater than his master.’

If they persecuted me, they will persecute you too; (456)

if they kept my word, they will keep yours too.

15:21 But they will do all this to you on account of my name

because they have no knowledge of the ONE who sent me.

15:22 If I had not come, had not spoken to them,

they would not have gone astray.

Now, they have no pretext (457) for their aberration.

15:23 The one fighting me with hatred

is hating my FATHER too.

15:24 If I had not done the works among them

which no one else did,

they would not be in their aberration.

Now, they have seen them,

and have fought with hatred both me and my FATHER.

15:25 But that the word might be fulfilled which is written in their Torah:

They hated me for no reason at all. (458)

In this passage, mention is made of the world order (15:18-19) and the synagogue 15:20-25; 16:1-4). The two verses 15:26-27 anticipate the next section.

{312} The keyword for the attitude of the world order towards the Messianic community is misein, “to hate.” (459) Since this is a political process, it is advisable to write “to fight with hate.” “To hate” alone would describe the emotion. The world order, Rome, can fight Messianism and does so consequently but dispassionately because it is vastly superior to its enemies. To mobilize its subjects for the dispassionate fight against the political enemies, they must be made to feel the passion of hatred. The hatred of the commissioners themselves is unemotional, completely rational, and calculated; the hatred of the performers is blind, must be downright blind so that the threshold of violence which is present in every living being can be crossed.

In the Psalms, the group of words “to hate, hater, hate” occurs very often. Here it is about more than envy, weariness, and jealousy between individual people; it is always about the enemies of Israel, to whom the “I” of the Psalms—Torah-abiding Israel—is almost hopelessly inferior. You can get an idea of this if you allow the following words to work on yourself, Psalm 139:21-22,

Your enemies, ETERNAL,

shouldn’t I hate them?

Who rebel against you,

Shouldn’t they disgust me?

With all my hatred, I hate them,

enemies they have become to me.

The reason for this “hate” is political enmity. Why does Rome treat the disciples as political enemies? Because it hated the Messiah “as the first,” because it had to fight the one who stands for the radical alternative to Rome “in principle” (this is how the word prōton can be paraphrased here), with extreme cruelty, just “with hate.”

The world order maintains friendly relations (ephilei) with those who think and act according to its orders and principles, which here means “from the world order” (ek tou kosmou). Why do the disciples not come “from the world order”? This is not self-evident. Rather, it would be natural for the disciples to behave like most other people who have adapted to the world order. Adaptation is the normal thing, it is often a sheer survival strategy.

Unadapted behavior, even more so unadapted political behavior is something astonishing and life-endangering. They are not adapted, not because they chose it them{313}selves, but because they were “chosen out of the world order,” the same words ek tou kosmou, but with a completely different thrust. To be chosen means: they were unexpectedly confronted with an alternative that they could not have considered of their own accord.

In the Scriptures, the chosen one is Israel, bechiri, “my chosen one,” Isaiah 43:20; 45:4; 65:15, etc. The verb “to choose,” bachar, is more frequently used in Deuteronomy and the Book of Isaiah (especially Isaiah 40-66). Both books aim at an unexpected new beginning, Isaiah 43:22; 44:1,

And not you called on me, Jacob,

would you have toiled for me, Israel?

. . .

But now listen, Jacob, my servant,

Israel: I choose it!

Or Deuteronomy 7:7-8,

Not because you are more than all nations

the NAME has attached itself to you,

he has chosen you,

because you are the least of all nations.

No, because he loved you . . .

The election is a sovereign act, like love; there are no legal claims and no rational reasons. You do not justify love. Therefore, agapan is to be translated here as “to love.” Only when he had “made a covenant with his chosen one” (Psalm 89:4), there are legal titles.

The election of the disciples is told by John in 1:37-51. Above all Nathanael makes that clear. He did not call for the Messiah, did not strive for a Messiah, rather, he says, nothing good can come from Nazareth. He sees and hears what he did not expect at all. A completely new political perspective can completely tear a human out of the course of events, he can begin a completely different life overnight; John’s formulation—“to be chosen out of the world order”—is thus very precise. (460) If the thought As the Lord, so the slave in 13:16 could perhaps demand a mere moral imitatio Christi, in 15:20 a common political fate is undoubtedly meant: common struggle, common fate: to be persecuted, to be hated.

{314} But now the subject changes, from “world order” to “they.” There can be no doubt that by this plural Rabbinical Judaism is meant. They “persecute, fight with hate, exclude from the synagogue, do not recognize.” The object is “the disciples,” the reason “because of my name.” The object of hatred, John interprets, is not so much the disciples, but rather the Messiah and the God of Israel, the FATHER.

To John, this is incomprehensible. He cannot understand why the synagogue behaves in such a way toward the Messianic community, and he includes himself among those who were hated for no reason in Israel, Psalms 35:19; 69:5 or Psalm 109:1 ff.,

God of my praise, do not be silent.

For the mouth of the criminal

and the mouth of deceit

open themselves against me.

Speeches of hatred surround me,

are waging war against me for no reason (dōrean, chinnam)!

Instead of love, they are a satan for me,

me—a prayer! (461)

They do evil to me instead of good,

hate instead of my love!

Without reason, chinnam, dōrean, in Israel is always a very serious reproach. Thus the Book of Job accuses the God of his fate of devouring the righteous without reason.

Rome’s hatred against the Messiah is not justified, but it is reasoned. This can be understood. The hatred of the synagogue is not rationally comprehensible to John. They have only “pretexts” (prophaseis) for this hateful fight. If the Messiah had not done these works, then . . .! But now it says with the psalm, “Hatred instead of my love.”

If anywhere, it is clear here that a rational discussion of political paths between ecclesia and synagogue has not been conducted; both are irrational for each other. In the case of Rome, you might understand this; it has reasons to “fight the Messiah with hatred.” But the Judeans. They have seen the works, “which no one else has done.” They fight him and us, says John, “without reason.”

We are not biased here. We only have to state that with the accusation “without reason” a conversation, let alone an understanding, becomes impossible. We observe that John does not want to look for reasons among his opponents—and the search for reasons on both sides would be the basic condition for a conversation be{315}tween both sides. John, for his part, assumes without any reason (!) that Rabbinical Judaism cannot have any reasons. He makes no effort at all here. The interpretation must state what is irrational in the vocable chinnam, dōrean, without being a party to this conflict.

↑ 13.5. The Farewell, 15:26-16:15

This passage is structured clearly and concisely:

“When he comes, the advocate” (hotan elthē ho paraklētos), 15:26;

“That one comes” (kai elthōn ekeinos), 16:8;

“When that one comes” (hotan de elthē ekeinos), 16:13.

↑ 13.5.1 “When he comes, the advocate, the inspiration of fidelity,” 15:26-16,7

15:26 When he comes, the advocate, whom I will send you from the FATHER

—the inspiration of fidelity that is going out from the FATHER—

that one will testify about me.

15:27 And you are testifying too

because you are with me from the beginning.

16:1 These things I have spoken to you so that you do not stumble. (462)

16:2 They will make you people without a synagogue,

in fact, the hour is coming when anyone who kills you will think

he is doing a work of public service for God. (463)

16:3 And they will do so because they recognized neither the FATHER nor me.

16:4 But this I have spoken to you

so that when their hour comes, you will remember what I said to you.

I did not say to you this from the beginning, because I was with you.

16:5 Now I am going away to the ONE who sent me,

and none of you is questioning me, ‘Where are you going?’

16:6 But because I have spoken these things to you,

the pain has filled your heart.

16:7 According to fidelity I say to you, (464)

{316} it is to your advantage that I go away,

for if I wouldn’t go away, the advocate will not come to you;

however, if I do go, I will send him to you.

The advocate (paraklētos) is sent by Jesus “from the Father.” He is the “inspiration of fidelity”; the adherence to God’s fidelity to Israel and to that exemplary concentration of Israel, which is the group (“the Twelve,” 6:67), inspires the disciples. The inspiration comes from the God of Israel; it does not bring a new world religion, but what is said and done with the word FATHER = God of Israel. This needs to be explained in more detail, and John does this in 16:13-15. Now it is about the testimony: That which comes from the God of Israel testifies of Jesus. And to this testimony, the disciples are enabled, “inspired.”

The word “beginning” plays a predominant role in the Gospel; “in the beginning” literally stands “at the beginning” of the text. John distinguishes between ex archēs and ap’ archēs. The first means “at the beginning” [in the temporal sense, 6:64; 16:4]; the second [in 15:27; cf. 8:44], it seems to me, is “from that beginning,” which is the basic principle of the Gospel (en archē, 1:1). The “principle” of the disciples is the Messiah, who is the “Word in the beginning,” the principle Word of the God of Israel. The testimony of the disciples is: Our principle is the Messianic epoch to come; this inspires our lives and aligns them because we are—in principle—with the Messiah. This is how the last words of 15:27 can be paraphrased. This also explains the present tense este, “you are.”

Rabbinical Judaism now makes the disciples people “without a synagogue” (aposynagōgoi). This, says Jesus, should not be a trap or a stumbling block for them, the word skandalon means both. The threat of expulsion is supposed to make impossible both—as a trap—the Messianic perspective, and— as a stumbling block—the walking on the chosen Messianic path.

The synagogue was not a church, not a religious community. Rather, it was both a place of assembly and an organ of self-government, where the children of Israel were able to manage their affairs within the framework of the status of an ethnic group recognized by the Romans with their permitted cult (religio licita, politeuma in Alexandria). This meant not insignificant protection against administrative sanctions and arbitrariness by the authorities. The degree of autonomy varied according to time, city, and region. (465) The synagogal status was something between full citizenship and the status of a stranger and an immigrant.

{317} But the status was precarious; there is ample evidence that privileges were confiscated and that there were expulsions and pogroms tolerated or even instigated by the authorities, such as the pogrom 37/38 in Alexandria. The synagogue, therefore, had to take care that groups with views hostile to the state did not gain the upper hand.